C# to C++ Tutorial - Part 2: Pointers Everywhere!

We still have a lot of ground to cover on pointers, but before we do, we need to address certain conceptual frameworks missing from C# that one must be intimately familiar with when moving to C++.

Specifically, in C# you mostly work with the Heap. The heap is not difficult to understand - its a giant lump of memory that you take chunks out of to allocate space for your classes. Anything using the new keyword is allocated on the heap, which ends up being almost everything in a C# program. However, the heap isn’t the only source of memory - there is also the Stack. The Stack is best described as what your program lives inside of. I’ve said before that everything takes up memory, and yes, that includes your program. The thing is that the Heap is inherently dynamic, while the Stack is inherently fixed. Both can be re-purposed to do the opposite, but trying to get the Stack to do dynamic allocation is extremely dangerous and is almost guaranteed to open up a mile-wide security hole.

I’m going to assume that a C# programmer knows what a stack is. All you need to understand is that absolutely every single piece of data that isn’t allocated on the heap is pushed or popped off your program’s stack. That’s why most debuggers have a “stack” of functions that you can go up and down. Understanding the stack in terms of how many functions you’re inside of is ok, but in reality, there are also variables declared on the stack, including every single parameter passed to a function. It is important that you understand how variable scope works so you can take advantage of declaring things on the stack, and know when your stack variables will simply vanish into nothingness. This is where { and } come in.

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

int bunny = 1;

{

int carrot=3;

int lettuce=8;

bunny = 2; // Legal

}

//carrot=2; //Compiler error: carrot does not exist

int carrot = 3; //Legal, since the other carrot no longer exists

{

int lettuce = 0;

{

//int carrot = 1; //Compiler error: carrot already defined

int grass = 9;

bunny = grass; //Still legal

bunny = carrot; // Also legal

}

//bunny = grass; //Illegal

bunny = lettuce; //Legal

}

//bunny = lettuce; //Illegal

}

{ and } define scope. Anything declared inside of them ceases to exist outside, but is still accessible to any additional layers of scope declared inside of them. This is a way to see your program’s stack in action. When bunny is declared, its pushed on to the stack. Then we enter our first scope area, where we push carrot and lettuce on to the stack and set bunny to 2, which is legal because bunny is still on the stack. When the scope is then closed, however, anything declared inside the scope is popped from the stack in the exact opposite order it was pushed on. Unfortunately, compiler optimization might change that order behind the scenes, so don’t rely on it, but it should be fairly consistent in debug builds. First lettuce is de-allocated (and its destructor called, if it has one), then carrot is de-allocated. Consequently, trying to set carrot to 2 outside of the scope will result in a compiler error, because it doesn’t exist anymore. This means we can now declare an entirely new integer variable that is also called carrot, without causing an error. If we visualize this as a stack, that means carrot is now directly above bunny. As we enter a new scope area, lettuce is then put on top of carrot, and then grass is put on top of lettuce. We can still assign either lettuce or carrot to bunny, since they are all on the stack, but once we leave this inner scope, grass is popped off the stack and no longer exists, so any attempt to use it causes an error. lettuce, however, is still there, so we can assign lettuce to bunny before the scope closes, which pops lettuce off the stack.Now the only things on the stack are bunny and carrot, in that order (if the compiler hasn’t moved things around). We are about to leave the function, and the function is also surrounded by { and }. This is because a function is, itself, a scope, so that means all variables declared inside of that scope are also destroyed in the order they were declared in. First carrot is destroyed, then bunny is destroyed, and then the function’s parameters argc and argv are destroyed (however the compiler can push those on to the stack in whatever order it wants, so we don’t know the order they get popped off), until finally the function itself is popped off the stack, which returns program flow to whatever called it. In this case, the function was main, so program flow is returned to the parent operating system, which does cleanup and terminates the process.

You can declare anything that has a size determined at compile time on the stack. This means if you have an array that has a constant size, you can declare it on the stack:

int array[5]; //Array elements are not initialized and therefore are undefined!

int array[5] = {0,0,0,0,0}; //Elements all initialized to 0

//int array[5] = {0}; // Compiler error - your initialization must match the array size

int array[] = {1,2,3,4}; //Declares an array of 4 ints on the stack initialized to 1,2,3,4

Class instance(arg1, arg2); //Calls a constructor with 2 arguments

Class instance; //Used if there are no arguments for the constructor

//Class instance(); //Causes a compiler error! The compiler will think its a function.

struct Simple

{

int a;

int b;

const char* str;

};

Simple instance = { 4, 5, "Sparkles" };

//instance.a is now 4

//instance.b is now 5

//instance.str is now "Sparkles"

int and double that don’t require a new statement to allocate, but otherwise forces you to use the Heap so its garbage collector can do the work.Wait a minute, stack variables automatically destroy themselves when they go out-of-scope, but how do you delete variables allocated from the Heap? In C#, you didn’t need to worry about this because of Garbage Collection, which everyone likes because it reduces memory leaks (but even I have still managed to cause a memory leak in C#). In C++, you must explicitly delete all your variables declared with the new keyword, and you must keep in mind which variables were declared as arrays and which ones weren’t. In both C# and C++, there are two uses of the new keyword - instantiating a single object, and instantiating an array. In C++, there are also two uses of the delete keyword - deleting a single object and deleting an array. You cannot mix up delete statements!

int* Fluffershy = new int();

int* ponies = new int[10];

delete Fluffershy; // Correct

//delete ponies; // WRONG, we should be using delete [] for ponies

delete [] ponies; // Just like this

//delete [] Fluffershy; // WRONG, we can't use delete [] on Fluffershy because we didn't

// allocate it as an array.

int* one = new int[1];

//delete one; // WRONG, just because an array only has one element doesn't mean you can

// use the normal delete!

delete [] one; // You still must use delete [] because you used new [] to allocate it.

[std::auto_ptr](http://www.cplusplus.com/reference/std/memory/auto_ptr/) takes advantage of this by taking ownership of a pointer and automatically deleting it when it is destroyed, so you can allocate the auto_ptr on the stack and benefit from the automatic destruction. However, in C++0x, this has been superseded by [std::unique_ptr](http://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/ee410601.aspx), which operates in a similar manner but uses some complex move semantics introduced in the new standard. I won’t go into detail about how to use these here as its out of the scope of this tutorial. Har har har.For those of you who like throwing exceptions, I should point out common causes of memory leaks. The most common is obviously just flat out forgetting to delete something, which is usually easily fixed. However, consider the following scenario:

void Kenny()

{

int* kenny = new int();

throw "BLARG";

delete kenny; // Even if the above exception is caught, this line of code is never reached.

}

int main(int argc, char* argv[])

{

try {

Kenny();

} catch(char * str) {

//Gotta catch'em all.

}

return 0; //We're leaking Kenny! o.O

}

int main(int argc, char* argv[])

{

int* kitty = new int();

*kitty=rand();

if(*kitty==0)

return 0; //LEAK

delete kitty;

return 0;

}

if statements may result in you forgetting what to delete. A good rule of thumb is to make sure you delete everything whenever you have a return statement. However, the opposite can also happen. If you are too vigilant about deleting everything, you might delete something you never allocated, which is just as bad:int main(int argc, char* argv[])

{

int* rarity = new int();

int* spike;

if(rarity==NULL)

{

spike=new int();

}

else

{

delete rarity;

delete spike; // Suddenly, in an alternate dimension, earth ceased to exist

return 0;

}

delete rarity; // Since this only happens if the allocation failed and returned a NULL

// pointer, this will also blow up.

delete spike;

return 0;

}

NULL pointer up there? Now that we’re familiar with memory management, we’re going to dig into pointers again, starting with the NULL pointer.Since a pointer points to a piece of memory that’s somewhere between 0 and 4294967295, what happens if its pointing at 0? Any pointer to memory location 0 is always invalid. All you need to know is that the operating system does some magic voodoo to ensure that any attempted access of memory location 0 will always throw an error, no matter what. 1, 2, 3, and any other double or single digit low numbers are also always invalid. 0xfdfdfdfd is what the VC++ debugger sets uninitialized memory to, so that pointer location is also always invalid. A pointer set to 0 is called a Null Pointer, and is usually used to signify that a pointer is empty. Consequently if an allocation function fails, it tends to return a null pointer. Null pointers are returned when the operation failed and a valid pointer cannot be returned. Consequently, you may see this:

int main(int argc, char* argv[])

{

int* blink = new int();

if(blink!=0) delete blink;

blink=0;

return 0;

}

NULL is defined as 0 in the standard library, so you could also say blink = NULL.Since pointers are just integers, we can do pointer arithmetic. What happens if you add 1 to a pointer? If you think of pointers as just integers, one would assume it would simply move the pointer forward a single byte.

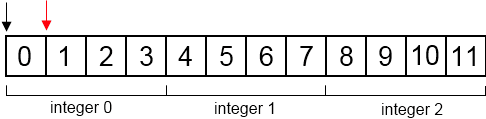

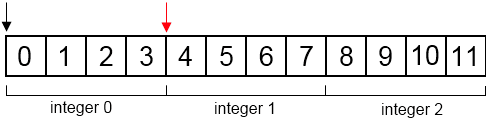

This isn’t what happens. Adding 1 to a pointer of type integer results in the pointer moving forward 4 bytes.

Adding or subtracting an integer $i$ from a pointer moves that pointer $i\cdot n$ bytes, where $n$ is the size, in bytes, of the pointer’s type. This results in an interesting parallel - adding or subtracting from a pointer is the same as treating the pointer as an array and accessing it via an index.

int main(int argc, char* argv[])

{

int* kitties = new int[14];

int* a = &kitties[7];

int* b = kitties+7; //b is now the same as a

int* c = &a[4];

int* d = b+4; //d is now the same as c

int* e = &kitties[11];

int* f = kitties+11;

//c,d,e, and f now all point to the same location

}

int main(int argc, char* argv[])

{

int* eggplants = new int[14];

int* a = &eggplants[7];

int* b = eggplants+10;

int diff = b-a; // Diff is now equal to 3

a += (diff*2); // adds 6 to a, making it point to eggplants[13]

diff = a-b; // diff is again equal to 3

diff = a-eggplants; //diff is now 13

++a; //The increment operator is valid on pointers, and operates the same way a += 1 would

// So now a points to eggplants[14], which is not a valid location, but this is still

// where the "end" of the array technically is.

diff = a-eggplants; // Diff now equals 14, the size of the array

--b; // Decrement works too

diff = a-b; // a is pointing to index 14, b is pointing to 9, so 14-9 = 5. Diff is now 5.

return 0;

}

integer to store the difference between the two pointers. What if one pointer was above 2147483647 and the other was at 0? The difference would overflow! Had I used an unsigned integer to store the difference, I’d have to be really damn sure that the left pointer was larger than the right pointer, or the negative value would also overflow. This complexity is why you have to goad windows into letting your program deal with pointer sizes over 2147483647.In addition to arithmetic, one can compare two pointers. We already know we can use == and !=, but we can also use < > <= and >=. While you can get away with comparing two completely unrelated pointers, these comparison operators are usually used in a context like the following:

int main(int argc, char* argv[])

{

int* teapots = new int[15];

int* end = teapots+15;

for(int* s = teapots; s<end; ++s)

*s = 0;

return 0;

}

void* is a legal pointer type, that any pointer type can be implicitly converted to. You can also explicitly cast void* to any pointer type you want, which is why you are allowed to explicitly cast any pointer type to another pointer type (int* p; short* q = (short*)p; is entirely legal). Doing so, however, is obviously dangerous. void* has its own problems, namely, how big is it? The answer is, you don’t know. Any attempt to use any kind of pointer arithmetic with a void* pointer will cause a compiler error. It is most often used when copying generic chunks of memory that only care about size in bytes, and not what is actually contained in the memory, like memcpy().int main(int argc, char* argv[])

{

int* teapots = new int[15];

void* p = (void*)teapots;

p++; // compiler error

unsigned short* d = (unsigned short*)p;

d++; // No compiler error, but you end up pointing to half an integer

d = (unsigned short*)teapots; // Still valid

return 0;

}

int[,] table = new int[4,5];

int unicorns[5][3]; // Well this seems perfectly reasonable, I wonder what-

int (*cthulu)[50] = new int[10][50]; // OH GOD GET IT AWAY GET IT AWAAAAAY...!

int c=5;

int (*cthulu)[50] = new int[c][50]; // legal

//int (*cthulu)[] = new int[10][c]; // Not legal. Only the leftmost parameter

// can be variable

//int (*cthulu)[] = new int[10][50]; // This is also illegal, the compiler is not allowed

// to infer the constant length of the array.

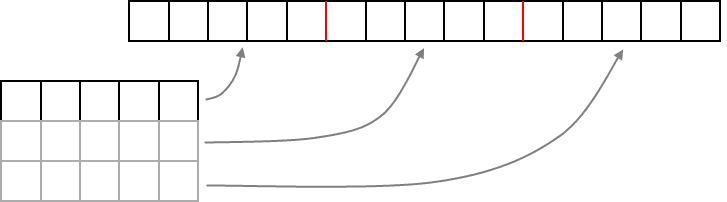

int**? Clearly if int* x is equivalent to int x[], shouldn’t int** x be equivalent to int x[][]? Well, it is - just look at the main() function, its got a multidimensional array in there that can be declared as just char** argv. The problem is that there are two kinds of multidimensional arrays - square and jagged. While both are accessed in identical ways, how they work is fundamentally different.Let’s look at how one would go about allocating a 3x5 square array. We can’t allocate a 3x5 chunk out of our computer’s memory, because memory isn’t 2-dimensional, its 1-dimensional. Its just freaking huge line of bytes. Here is how you squeeze a 2-dimensional array into a 1-dimensional line:

As you can see, we just allocate each row right after the other to create a 15-element array ($5\cdot 3 = 15$). But then, how do we access it? Well, if it has a width of 5, to access another “row” we’d just skip forward by 5. In general, if we have an $n$ by $m$ multidimensional array being represented as a one-dimensional array, the proper index for a coordinate $(x,y)$ is given by: array[x + (y*n)]. This can be extended to 3D and beyond but it gets a little messy. This is all the compiler is really doing with multidimensional array syntax - just automating this for you.

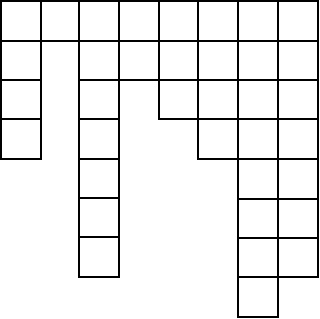

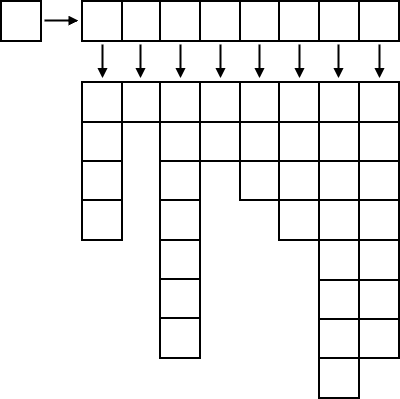

Now, if this is a square array (as evidenced by it being a square in 2D or a cube in 3D), a jagged array is one where each array is a different size, resulting in a “jagged” appearance:

We can’t possibly allocate this in a single block of memory unless we did a lot of crazy ridiculous stuff that is totally unnecessary. However, given that arrays in C++ are just pointers to a block of memory, what if you had a pointer to a block of memory that was an array of pointers to more blocks of memory?

Suddenly we have our jagged array that can be accessed just like our previous arrays. It should be pointed out that with this format, each inner-array can be in a totally random chunk of memory, so the last element could be at position 200 and the first at position 5 billion. Consequently, pointer arithmetic only makes sense within each column. Because this is an array of arrays, we declare it by creating an array of pointers. This, however, does not initialize the entire array; all we have now is an array of illegal pointers. Since each array could be a different size than the other arrays (this being the entire point of having a jagged array in the first place), the only possible way of initializing these arrays is individually, often by using a for loop. Luckily, the syntax for accessing jagged arrays is the exact same as with square arrays.

int main(int argc, char* argv[])

{

int** jagged = new int*[5]; //Creates an array of 5 pointers to integers.

for(int i = 0; i < 5; ++i)

{

jagged[i] = new int[3+i]; //Assigns each pointer to a new array of a unique size

}

jagged[4][1]=0; //Now we can assign values directly, or...

int* second = jagged[2]; //Pull out one column, and

second[0]=0; //manipulate it as a single array

// The double-access works because of the order of operations. Since [] is just an

// operator, it is evaluated from left to right, like any other operator. Here it is

// again, but with the respective types that each operator resolves to in parenthesis.

( (int&) ( (int*&) jagged[4] ) [1] ) = 0;

}

jagged[2] = (int*)kitty. However, until C++0x, those references didn’t have any meaningful data type, so even though the compiler was using int*&, using that in your code will throw a compiler error in older compilers. If you need to make your code work in non-C++0x compilers, you can simply avoid using references to pointers and instead use a pointer to a pointer.int* bunny;

int* value = new int[5];

int*& bunnyref = bunny; // Throws an error in old compilers

int** pbunny = &bunny; // Will always work

bunnyref = value; // This does the same exact thing as below.

*pbunny = value;

// bunny is now equal to value

What about pointers to functions? I'm having trouble understanding why this doesn't work:

char* Test()

{

char cstm[] = { 'T', 'E', 'S', 'T', '\n' };

return cstm;

}

int _tmain(int argc, _TCHAR* argv[])

{

char* (*funcP)() = &Test;

char* convPntr = (*funcP)();

//Why don't I see a "T" on the screen?

::printf("Character: %c", convPntr[0]);

}

I have deliberately not covered pointers to functions yet. I intend to cover them by comparing them to C# delegates at a later point.

As for why you don't see a 'T' on the screen, it has nothing to do with function pointers - You are not thinking with the stack. You must remember that all functions are scopes. This is easy to remember because anything inside { } is a scope, and that includes a function. That means, like all other scopes, any variable declared on the stack inside a function ceases to exist outside of that function. Your code here is referencing a variable that no longer exists. You can't return a pointer to a variable declared on the stack inside a function because once the function exits, cstm[] no longer exists because it is now out of scope, so the pointer is pointing to garbage memory.

Also your string doesn't have a null terminator, either, which is an even more elementary problem. This is why you usually don't use an array on the stack to store strings, you just define a constant "TEST\n" and throw around a pointer to it, which the compiler does for you when you say const char* val="TEST\n";

Thanks for the explanation... I see my problem now. If I would have placed the return value of Test() in a character var instead of a pointer, that would have worked, right? Because then it would take the return value of the Test() function and copy it to the character var before "cstm" itself goes out of scope.

I didn't understand why you said my string doesn't have a null terminator though...?

char cstm[] = { 'T', 'E', 'S', 'T', '\n' };

I defined the last character as a null terminator?

'\n' is a newline character. '\0' or simply 0 is a null terminator.

lol.... yes, I feel like an idiot.

More.....Is there pointer in C# like C or C++ ?

Ling