It's standard procedure at the University of Washington to allow a single sheet of handwritten notes during a Mathematics exam. I started collecting these sheets after I realized how useful it was to have a reference that basically summarized all the useful parts of the course on a single sheet of paper. Now that I've graduated, it's easy for me to quickly forget all the things I'm not using. The problem is that, when I need to say, develop an algorithm for simulating turbulent airflow, I need to go back and re-learn vector calculus, differential equations and nonlinear dynamics. So I've decided to digitize all my notes and put them in one place where I can reference them. I've uploaded it here in case they come in handy to anyone else.

The earlier courses listed here had to be reconstructed from my class notes because I'd thrown my final notesheet away or otherwise lost it. The classes are not listed in the order I took them, but rather organized into related groups. This post may be updated later with expanded explanations for some concepts, but these are highly condensed notes for reference, and a lot of it won't make sense to someone who hasn't taken a related course.

Math 124 - Calculus IlostMath 125 - Calculus IIlostMath 126 - Calculus IIIlostMath 324 - Multivariable Calculus I\[ r^2 = x^2 + y^2 \]

\[ x= r\cos\theta \]

\[ y=r\sin\theta \]

\[ \iint\limits_R f(x,y)\,dA = \int_\alpha^\beta\int_a^b f(r\cos\theta,r\sin\theta)r\,dr\,d\theta=\int_\alpha^\beta\int_{h_1(\theta}^{h_2(\theta)} f(r\cos\theta,r\sin\theta)r\,dr\,d\theta \]

\[ m=\iint\limits_D p(x,y)\,dA \begin{cases} \begin{aligned} M_x=\iint\limits_D y p(x,y)\,dA & \bar{x}=\frac{M_y}{m}=\frac{1}{m}\iint x p(x,y)\,dA \end{aligned} \\ \begin{aligned} M_y=\iint\limits_D x p(x,y)\,dA & \bar{y}=\frac{M_x}{m}=\frac{1}{m}\iint y p(x,y)\,dA \end{aligned} \end{cases} \]

\[ Q = \iint\limits_D \sigma(x,y)\,dA \]

\[ I_x = \iint\limits_D y^2 p(x,y)\,dA \]

\[ I_y = \iint\limits_D x^2 p(x,y)\,dA \]

\[ I_0 = \iint\limits_D (x^2 + y^2) p(x,y)\,dA \]

\[ \iiint f(x,y,z) dV = \lim_{l,m,n\to\infty}\sum_{i=1}^l\sum_{j=1}^m\sum_{k=1}^n f(x_i,y_j,z_k) \delta V \]

\[ \iiint\limits_B f(x,y,z)\,dV=\int_r^s\int_d^c\int_a^b f(x,y,z)\,dx\,dy\,dz = \int_a^b\int_r^s\int_d^c f(x,y,z)\,dy\,dz\,dx \]

$$E$$ = general bounded region

Type 1: $$E$$ is between graphs of two continuous functions of $$x$$ and $$y$$.

\[ E=\{(x,y,z)|(x,y)\in D, u_1(x,y) \le z \le u_2(x,y)\} \]

$$D$$ is the projection of E on to the xy-plane, where

\[ \iiint\limits_E f(x,y,z)\,dV = \iint\limits_D\left[\int_{u_1(x,y)}^{u_2(x,y)} f(x,y,z)\,dz \right]\,dA \]

$$D$$ is a type 1 planar region:

\[ \iiint\limits_E f(x,y,z)\,dV = \int_a^b \int_{g_1(x)}^{g_2(x)} \int_{u_1(x,y)}^{u_2(x,y)} f(x,y,z)\,dz\,dy\,dx \]

$$D$$ is a type 2 planar region:

\[ \iiint\limits_E f(x,y,z)\,dV = \int_d^c \int_{h_1(y)}^{h_2(y)} \int_{u_1(x,y)}^{u_2(x,y)} f(x,y,z)\,dz\,dx\,dy \]

Type 2: $$E$$ is between $$y$$ and $$z$$, $$D$$ is projected on to $$yz$$-plane

\[ E=\{(x,y,z)|(y,z)\in D, u_1(y,z) \le x \le u_2(y,z)\} \]

\[ \iiint\limits_E f(x,y,z)\,dV = \iint\limits_D\left[\int_{u_1(y,z)}^{u_2(y,z)} f(x,y,z)\,dx \right]\,dA \]

Type 3: $$E$$ is between $$x$$ and $$z$$, $$D$$ is projected on to $$xz$$-plane

\[ E=\{(x,y,z)|(x,z)\in D, u_1(x,z) \le y \le u_2(x,z)\} \]

\[ \iiint\limits_E f(x,y,z)\,dV = \iint\limits_D\left[\int_{u_1(x,z)}^{u_2(x,z)} f(x,y,z)\,dy \right]\,dA \]

Mass

\[ m = \iiint\limits_E p(x,y,z)\,dV \]

\[ \bar{x} = \frac{1}{m}\iiint\limits_E x p(x,y,z)\,dV \]

\[ \bar{y} = \frac{1}{m}\iiint\limits_E y p(x,y,z)\,dV \]

\[ \bar{z} = \frac{1}{m}\iiint\limits_E z p(x,y,z)\,dV \]

Center of mass: $$(\bar{x},\bar{y},\bar{z})$$

\[ Q = \iiint\limits_E \sigma(x,y,z)\,dV \]

\[ I_x = \iiint\limits_E (y^2 + z^2) p(x,y,z)\,dV \]

\[ I_y = \iiint\limits_E (x^2 + z^2) p(x,y,z)\,dV \]

\[ I_z = \iiint\limits_E (x^2 + y^2) p(x,y,z)\,dV \]

Spherical Coordinates:

\[ z=p\cos\phi \]

\[ r=p\sin\phi \]

\[ dV=p^2\sin\phi \]

\[ x=p\sin\phi\cos\theta \]

\[ y=p\sin\phi\sin\theta \]

\[ p^2 = x^2 + y^2 + z^2 \]

\[ \iiint\limits_E f(x,y,z)\,dV = \int_c^d\int_\alpha^\beta\int_a^b f(p\sin\phi\cos\theta,p\sin\phi\sin\theta,p\cos\phi) p^2\sin\phi\,dp\,d\theta\,d\phi \]

Jacobian of a transformation $$T$$ given by $$x=g(u,v)$$ and $$y=h(u,v)$$ is:

\[ \begin{aligned} \frac{\partial (x,y)}{\partial (u,v)} = \begin{vmatrix} \frac{\partial x}{\partial u} & \frac{\partial x}{\partial v} \\[0.1em] \frac{\partial y}{\partial u} & \frac{\partial y}{\partial v} \end{vmatrix} = \frac{\partial x}{\partial u} \frac{\partial y}{\partial v} - \frac{\partial x}{\partial v} \frac{\partial y}{\partial u} \end{aligned} \]

Given a transformation T whose Jacobian is nonzero, and is one to one:

\[ \iint\limits_R f(x,y)\,dA = \iint\limits_S f\left(x(u,v),y(u,v)\right)\left|\frac{\partial (x,y)}{\partial (u,v)}\right|\,du\,dv \]

Polar coordinates are just a special case:

\[ x = g(r,\theta)=r\cos\theta \]

\[ y = h(r,\theta)=r\sin\theta \]

\[ \frac{\partial (x,y)}{\partial (u,v)} = \begin{vmatrix} \frac{\partial x}{\partial r} & \frac{\partial x}{\partial \theta} \\ \frac{\partial y}{\partial r} & \frac{\partial y}{\partial \theta} \end{vmatrix} = \begin{vmatrix} \cos\theta & -r\sin\theta \\ \sin\theta & r\cos\theta \end{vmatrix} = r\cos^2\theta + r\sin^2\theta=r(\cos^2\theta + \sin^2\theta) = r \]

\[ \iint\limits_R f(x,y)\,dx\,dy = \iint\limits_S f(r\cos\theta, r\sin\theta)\left|\frac{\partial (x,y)}{\partial (u,v)}\right|\,dr\,d\theta=\int_\alpha^\beta\int_a^b f(r\cos\theta,r\sin\theta)|r|\,dr\,d\theta\]

For 3 variables this expands as you would expect: $$x=g(u,v,w)$$ $$y=h(u,v,w)$$ $$z=k(u,v,w)$$

\[ \frac{\partial (x,y,z)}{\partial (u,v,w)}=\begin{vmatrix} \frac{\partial x}{\partial u} & \frac{\partial x}{\partial v} & \frac{\partial x}{\partial w} \\ \frac{\partial y}{\partial u} & \frac{\partial y}{\partial v} & \frac{\partial y}{\partial w} \\ \frac{\partial z}{\partial u} & \frac{\partial z}{\partial v} & \frac{\partial z}{\partial w} \end{vmatrix} \]

\[ \iiint\limits_R f(x,y,z)\,dV = \iiint\limits_S f(g(u,v,w),h(u,v,w),k(u,v,w)) \left|\frac{\partial (x,y,z)}{\partial (u,v,w)} \right| \,du\,dv\,dw\]

Line IntegralsParameterize: $$r(t)=\langle x(t),y(t),z(t) \rangle$$ where $$r'(t)=\langle x'(t),y'(t),z'(t) \rangle$$ and $$|r'(t)|=\sqrt{x'(t)^2 + y'(t)^2 + z'(t)^2} $$

\[ \int_C f(x,y,z)\,ds = \int_a^b f(r(t))\cdot |r'(t)|\,dt = \int_a^b f(x(t),y(t),z(t))\cdot\sqrt{x'(t)^2 + y'(t)^2 + z'(t)^2}\,dt\;\;\;a<t<b \]

For a vector function $$\mathbf{F}$$:

\[ \int_C \mathbf{F}\cdot dr = \int_a^b \mathbf{F}(r(t))\cdot r'(t)\,dt \]

Surface Integrals\[ \]

Parameterize: $$r(u,v) = \langle x(u,v),y(u,v),z(u,v) \rangle$$

\[ \begin{matrix} r_u=\frac{\partial x}{\partial u}\vec{\imath} + \frac{\partial y}{\partial u}\vec{\jmath} + \frac{\partial z}{\partial u}\vec{k} \\ r_v=\frac{\partial x}{\partial v}\vec{\imath} + \frac{\partial y}{\partial v}\vec{\jmath} + \frac{\partial z}{\partial v}\vec{k} \end{matrix}\]

\[ r_u \times r_v = \begin{vmatrix} \vec{\imath} & \vec{\jmath} & \vec{k} \\ \frac{\partial x}{\partial u} & \frac{\partial y}{\partial u} & \frac{\partial z}{\partial u} \\ \frac{\partial x}{\partial v} & \frac{\partial y}{\partial v} & \frac{\partial z}{\partial v} \end{vmatrix} \]

\[ \iint\limits_S f(x,y,z) dS = \iint\limits_D f(r(t))|r_u \times r_v|\,dA \]

For a vector function $$\mathbf{F}$$:

\[ \iint\limits_S \mathbf{F}\cdot dr = \iint\limits_D \mathbf{F}(r(u,v))\cdot (r_u \times r_v)\,dA) \]

Any surface $$S$$ with $$z=g(x,y)$$ is equivalent to $$x=x$$, $$y=y$$, and $$z=g(x,y)$$, so

$$xy$$ plane:

\[ \iint\limits_S f(x,y,z)\,dS = \iint\limits_D f(x,y,g(x,y))\sqrt{\left(\frac{\partial z}{\partial x}\right)^2+\left(\frac{\partial z}{\partial y}\right)^2+1}\,dA \]

$$yz$$ plane:

\[ \iint\limits_S f(x,y,z)\,dS = \iint\limits_D f(x,h(x,z),z)\sqrt{\left(\frac{\partial y}{\partial x}\right)^2+\left(\frac{\partial y}{\partial z}\right)^2+1}\,dA \]

$$xz$$ plane:

\[ \iint\limits_S f(x,y,z)\,dS = \iint\limits_D f(g(y,z),y,z)\sqrt{\left(\frac{\partial x}{\partial y}\right)^2+\left(\frac{\partial x}{\partial z}\right)^2+1}\,dA \]

Flux:

\[ \iint\limits_S\mathbf{F}\cdot dS = \iint\limits_D\mathbf{F}\cdot (r_u \times r_v)\,dA \]

The gradient of $$f$$ is the vector function $$\nabla f$$ defined by:

\[ \nabla f(x,y)=\langle f_x(x,y),f_y(x,y)\rangle = \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}\vec{\imath} + \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}\vec{\jmath} \]

Directional Derivative:

\[D_u\,f(x,y) = f_x(x,y)a + f_y(x,y)b = \nabla f(x,y)\cdot u \text{ where } u = \langle a,b \rangle \]

\[ \int_C\,ds=\int_a^b |r'(t)|=L \]

\[ \]

If $$\nabla f$$ is conservative, then:

\[ \int_{c_1} \nabla f\,dr=\int_{c_2} \nabla f\,dr \]

This means that the line integral between two points will always be the same, no matter what curve is used to go between the two points - the integrals are path-independent and consequently only depend on the starting and ending positions in the conservative vector field.

A vector function is conservative if it can be expressed as the gradient of some potential function $$\psi$$: $$\nabla \psi = \mathbf{F}$$

\[ curl\,\mathbf{F} =\nabla\times\mathbf{F}\]

\[ div\,\mathbf{F} =\nabla\cdot\mathbf{F}\]

Math 326 - Multivariable Calculus II$$f(x,y)$$ is continuous at a point $$(x_0,y_0)$$ if

\[ \lim\limits_{(x,y)\to(0,0)} f(x,y) = f(x_0,y_0) \]

$$f+g$$ is continuous if $$f$$ and $$g$$ are continuous, as is $$\frac{f}{g}$$ if $$g \neq 0$$

A composite function of a continuous function is continuous

\[ \frac{\partial f}{\partial x} = f_x(x,y) \]

\[ \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}\bigg|_{(x_0,y_0)}=\left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}\right)_{(x_0,y_0)}=f_x(x_0,y_0) \]

To find $$\frac{\partial z}{\partial x} F(x,y,z)$$, differentiate $$x$$ as normal, hold y constant, and differentiate $$z$$ as a function (such that $$z^2 = 2z \frac{\partial z}{\partial x}$$ and $$2z = 2 \frac{\partial z}{\partial x}$$)

Ex:

\[ F(x,y,z) = \frac{x^2}{16} + \frac{y^2}{12} + \frac{z^2}{9} = 1 \]

\[ \frac{\partial z}{\partial x} F = \frac{2x}{16} + \frac{2z}{}\frac{\partial z}{\partial x} = 0 \]

The tangent plane of $$S$$ at $$(a,b,c): z-c = f_x(a,b)(x-a) + f_y(a,b)(y-b)$$ where $$z=f(x,y)$$, or $$z =f(a,b) + f_x(a,b)(x-a) + f_y(a,b)(y-b)$$

Note that

\[ f_x(a,b)=\frac{\partial z}{\partial x}\bigg|_{(a,b)} \]

which enables you to find tangent planes implicitly.

Set $$z=f(x,y)$$. $$f_x=f_y=0$$ at a relative extreme $$(a,b)$$.

Distance from origin:

\[ D^2 = z^2 + y^2 + x^2 = f(a,b)^2 + y^2 + x^2 \]

Minimize $$D$$ to get point closest to the origin.

The differential of $$f$$ at $$(x,y)$$:

\[ df(x,y;dx,dy)=f_x(x,y)\,dx + f_y(x,y)\,dy \]

\[ dz=\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}\,dx + \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}\,dy \]

$$f$$ is called differentiable at $$(x,y)$$ if it $$s$$ defined for all points near $$(x,y)$$ and if there exists numbers $$A$$,$$B$$ such that

\[ \lim_{(n,k)\to(0,0)}\frac{|f(x+h,y+k) - f(x,y) - Ah - Bk|}{\sqrt{h^2 + k^2}}=0 \]

If $$f$$ is differentiable at $$(x,y)$$ it is continuous there.

\[ A = f_x(x,y) \]

and

\[ B=f_y(x,y) \]

If $$F_x(x,y)$$ and $$F_y(x,y)$$ are continuous at a point $$(x_0,y_0)$$ defined in $$F$$, then $$F$$ is differentiable there.

Ex: The differential of $$f(x,y)=3x^2y+2xy^2+1$$ at $$(1,2)$$ is $$df(1,2;h,k)=20h+11k$$

\[ d(u+v)=du+dv \]

\[ d(uv)=u\,dv + v\,du \]

\[ d\left(\frac{u}{v}\right)=\frac{v\,du -u\,dv}{v^2} \]

Taylor Series:

\[ f^{(n)}(t)=\left[\left(h\frac{}{} + k\frac{}{})^n F(x,y) \right) \right]_{x=a+th,y=b+tk} \]

Note:

\[ f''(t)=h^2 F_{xx} + 2hk F_{xy} + k^2 F_{yy} \]

\[ \begin{matrix} x=f(u,v) \\ y=g(u,v) \end{matrix} \]

\[ J=\frac{\partial(f,g)}{\partial(u,v)} \]

\[ \begin{matrix} u=F(x,y) \\ v=G(x,y) \end{matrix} \]

\[ j = J^{-1} = \frac{1}{\frac{\partial(f,g)}{\partial(u,v)}} \]

\[ \begin{matrix} x = u-uv \\ y=uv \end{matrix} \]

\[ \iint\limits_R\frac{dx\,dy}{x+y} \]

R bounded by

\[ \begin{matrix} x+y=1 & x+y=4 \\ y=0 & x=0 \end{matrix}\]

\[ \int_0^1\int_0^x \frac{du\,dv}{u-uv+ux}\left|\frac{\partial(x,y)}{\partial(u,v)}\right| \]

\[ \frac{\partial(F,G)}{\partial(u,v)}=\begin{vmatrix} \frac{\partial F}{\partial u} & \frac{\partial F}{\partial v} \\ \frac{\partial G}{\partial u} & \frac{\partial G}{\partial v} \end{vmatrix} \]

\[ \nabla f = \langle f_x, f_y, f_z \rangle \]

\[ G_x(s_0,t_0) =F_x(a,b)f_x(s_0,t_0) + F_y(a,b)g_x(s_0,t_0) \]

\[ U\times V = U_xV_y - U_yV_x \text{ or } A\times B = \left\langle \begin{vmatrix} a_y & a_z \\ b_y & b_z \end{vmatrix}, -\begin{vmatrix} a_x & a_z \\ b_x & b_z \end{vmatrix}, \begin{vmatrix} a_x & a_y \\ b_x & b_y \end{vmatrix} \right\rangle \]

Given $$G(s,t)=F(f(s,t),g(s,t))$$, then:

\[ \begin{matrix} \frac{\partial G}{\partial s} = \frac{\partial F}{\partial x}\frac{\partial f}{\partial s} + \frac{\partial F}{\partial y}\frac{\partial g}{\partial s} \\ \frac{\partial G}{\partial t} = \frac{\partial F}{\partial x}\frac{\partial f}{\partial t} + \frac{\partial F}{\partial y}\frac{\partial g}{\partial t} \end{matrix} \]

Alternatively, $$ u=F(x,y,z)=F(f(t),g(t),h(t))$$ yields

\[ \frac{du}{dt}=\frac{\partial u}{\partial x}\frac{dx}{dt} + \frac{\partial u}{\partial y}\frac{dy}{dt} + \frac{\partial u}{\partial z}\frac{dz}{dt} \]

Examine limit along line $$y=mx$$:

\[ \lim_{x\to 0} f(x,mx) \]

If $$g_x$$ and $$g_y$$ are continuous, then $$g$$ is differentiable at that point (usually $$0,0$$).

Notice that if $$f_x(0,0)=0$$ and $$f_y(0,0)=0$$ then $$df(0,0;h,l)=0h+0k=0$$

The graph of $$y(x,y)$$ lies on a level surface $$F(x,y,z)=c$$ means $$f(x,y(x,z),z)=c$$. So then use the chain rule to figure out the result in terms of $$F$$ partials by considering $$F$$ a composite function $$F(x,y(x,z),z)$$.

Fundamental implicit function theorem: Let $$F(x,y,z)$$ be a function defined on an open set $$S$$ containing the point $$(x_0,y_0,z_0)$$. Suppose $$F$$ has continuous partial derivatives in $$S$$. Furthermore assume that: $$F(x_0,y_0,z_0)=0, F_z(x_0,y_0,z_0)\neq 0$$. Then $$z=f(x,y)$$ exists, is continuous, and has continuous first partial derivatives.

\[ f_x = -\frac{F_x}{F_z} \]

\[ f_y = -\frac{F_y}{F_z} \]

Alternatively, if

\[ \begin{vmatrix} F_x & F_y \\ G_x & G_y \end{vmatrix} \neq 0 \]

, then we can solve $$x$$ and $$y$$ as functions of $$z$$. Since the cross-product is made of these determinants, if the $$x$$ component is nonzero, you can solve $$y,z$$ as functions of $$x$$, and therefore graph it on the $$x-axis$$.

To solve level surface equations, let $$F(x,y,z)=c$$ and $$G(x,y,z)=d$$, then use the chain rule, differentiating by the remaining variable (e.g. $$\frac{dy}{dx}$$ and $$\frac{dz}{dx}$$ means do $$x$$)

\[ \begin{matrix} F_x + F_y y_x + F_z z_x = 0 \\ G_x + G_y y_x + G_z z_x = 0 \end{matrix} \]

if you solve for $$y_x$$,$$z_x$$, you get

\[ \left[ \begin{matrix} F_y & F_z \\ G_y & G_z \end{matrix} \right] \left[ \begin{matrix} y_x \\ z_x \end{matrix} \right] = \left[\begin{matrix}F_x \\ G_x \end{matrix} \right] \]

Mean value theorem:

\[ f(b) - f(a) = (b-a)f'(X) \]

\[ a < X < b \]

or:

\[ f(a+h)=f(a)+hf'(a + \theta h) \]

\[ 0 < \theta < 1 \]

xy-plane version:

\[ F(a+h,b+k)-F(a,b)=h F_x(a+\theta h,b+\theta k)+k F_y(a+\theta h, b+\theta k) \]

\[ 0 < \theta < 1 \]

Lagrange Multipliers: $$\nabla f = \lambda\nabla g$$ for some scale $$\lambda$$ if $$(x,y,z)$$ is a minimum:

\[ f_x=\lambda g_x \]

\[ f_y=\lambda g_y \]

\[ f_z=\lambda g_z \]

Set $$f=x^2 + y^2 + z^2$$ for distance and let $$g$$ be given.

Math 307 - Introduction to Differential EquationslostMath 308 - Matrix AlgebralostMath 309 - Linear AnalysislostAMath 353 - Partial Differential EquationsFourier Series:

\[ f(x)=b_0 + \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \left(a_n \sin\frac{n\pi x}{L} + b_n\cos\frac{n\pi x}{L} \right) \]

\[ b_0 = \frac{1}{2L}\int_{-L}^L f(y)\,dy \]

\[ a_m \frac{1}{L}\int_{-L}^L f(y) \sin\frac{m\pi y}{L}\,dy \]

\[ b_m = \frac{1}{L}\int_{-L}^L f(y)\cos\frac{m\pi y}{L}\,dy \]

\[ m \ge 1 \]

\[ u_t=\alpha^2 u_{xx} \]

\[ \alpha^2 = \frac{k}{pc} \]

\[ u(x,t)=F(x)G(t) \]

Dirichlet: $$u(0,t)=u(L,t)=0$$

Neumann:$$u_x(0,t)=u_x(L,t)=0$$

Robin:$$a_1 u(0,t)+b_1 u_x(0,t) = a_2 u(L,t) + b_2 u_x(L,t) = 0$$

Dirichlet:

\[ \lambda_n=\frac{n\pi}{L}\;\;\; n=1,2,... \]

\[ u(x,t)=\sum_{n=1}^{\infty} A_n \sin\left(\frac{n\pi x}{L} \right)\exp\left(-\frac{n^2\alpha^2\pi^2 t}{L^2}\right) \]

\[ A_n = \frac{2}{L} \int_0^L f(y) \sin\frac{n\pi y}{L}\,dy = 2 a_m\text{ for } 0\text{ to } L \]

Neumann:

\[ \lambda_n=\frac{n\pi}{L}\;\;\; n=1,2,... \]

\[ u(x,t)=B_0 + \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} B_n \cos\left(\frac{n\pi x}{L} \right)\exp\left(-\frac{n^2\alpha^2\pi^2 t}{L^2}\right) \]

\[ B_0 = \frac{1}{L} \int_0^L f(y)\,dy \]

\[ B_n = \frac{2}{L} \int_0^L f(y) \cos\frac{n\pi y}{L}\,dy = 2 b_m\text{ for } 0\text{ to } L \]

Dirichlet/Neumann:

\[ \lambda_n=\frac{\pi}{2L}(2n + 1)\;\;\; n=0,1,2,... \]

\[ u(x,t)=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} A_n \sin\left(\lambda_n x\right) \exp\left(-\alpha^2 \lambda_n^2 t\right) \]

\[ A_n = \frac{2}{L} \int_0^L f(y) \sin\left(\lambda_n y\right)\,dy \]

Neumann/Dirichlet:

\[ \lambda_n=\frac{\pi}{2L}(2n + 1)\;\;\; n=0,1,2,... \]

\[ u(x,t)=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} B_n \cos\left(\lambda_n x\right) \exp\left(-\alpha^2 \lambda_n^2 t\right) \]

\[ B_n = \frac{2}{L}\int_0^L f(y)\cos(\lambda_n y)\,dy \]

\[ v_2(x,y)=\sum_{n=1}^{\infty} C_n(t)[\sin/\cos](\lambda_n x) \]

Replace $$[\sin/\cos]$$ with whatever was used in $$u(x,t)$$

\[ C_n(t)=\int_0^t p_n(s) e^{\lambda_n^2\alpha^2 (s-t)}\,ds \]

\[ p_n(t)=\frac{2}{L}\int_0^L p(y,t)[\sin/\cos](\lambda_n y)\,dy \]

Replace $$[\sin/\cos]$$ with whatever was used in $$u(x,t)$$. Note that $$\lambda_n$$ for $$C_n$$ and $$p_n(t)$$ is the same as used for $$u_1(x,t)$$

Sturm-Liouville:

\[ p(x)\frac{d^2}{dx^2}+p'(x)\frac{d}{dx}+q(x) \]

\[ a_2(x)\frac{d^2}{dx^2} + a_1(x)\frac{d}{dx} + a_0(x) \rightarrow p(x)=e^{\int\frac{a_1(x)}{a_2(x)}\,dx}\]

\[ q(x)=p(x)\frac{a_0(x)}{a_2(x)} \]

Laplace's Equation:

\[ \nabla^2 u=0 \]

\[ u=F(x)G(y) \]

\[ \frac{F''(x)}{F(x)} = -\frac{G''(y)}{G(y)} = c \]

for rectangular regions

\[ F_?(x)=A =\sinh(\lambda x) + B \cosh(\lambda x) \]

use odd $$\lambda_n$$ if $$F$$ or $$G$$ equal a single $$\cos$$ term.

\[ G_?(y)=C =\sinh(\lambda y) + D \cosh(\lambda y) \]

\[ u(x,?)=G(?) \]

\[ u(?,y)=F(y) \]

Part 1: All $$u_?(x,?)=0$$

\[ \lambda_n=\frac{n\pi}{L y}\text{ or }\frac{(2n+1)\pi}{2L y} \]

\[ u_1(x,y)=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}A_n F_1(x)G_1(y) \]

\[ A_n = \frac{2}{L_y F_1(?)}\int_0^{L_y} u(?,y)G_1(y)\,dy \]

\[ u(?,y)=h(y) \]

\[ ? = L_x\text{ or }0 \]

Part 2: All $$u_?(?,y)=0$$

\[ \lambda_n=\frac{n\pi}{L x}\text{ or }\frac{(2n+1)\pi}{2L x} \]

\[ u_2(x,y)=\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}B_n F_2(x)G_2(y) \]

\[ B_n = \frac{2}{L_x G_2(?)}\int_0^{L_x} u(x,?)F_2(x)\,dx \]

\[ u(x,?)=q(x) \]

\[ ? = L_y\text{ or }0 \]

\[ u(x,y)=u_1(x,y)+u_2(x,y) \]

Circular $$\nabla^2 u$$:

\[ u_{rr} + \frac{1}{r} u_r + \frac{1}{r^2}u_{\theta \theta} = 0 \]

\[ \frac{G''(\theta)}{G(\theta)}= - \frac{r^2 F''(r) + r F(r)}{F(r)} = c\]

\[ \left\langle f,g \right\rangle = \int_a^b f(x) g(x)\,dx \]

\[ \mathcal{L}_s=-p(x)\frac{d^2}{dx^2}-p'(x)\frac{d}{dx} + q(x) \]

\[ \mathcal{L}_s\phi(x)=\lambda r(x) \phi(x) \]

\[ \left\langle\mathcal{L}_s y_1,y_2 \right\rangle =\int_0^L \left(-[p y_1']'+q y_1\right)y_2\,dx \]

$$\mathcal{L}_s = f(x)$$, then $$\mathcal{L}_s^{\dagger} v(x) = 0$$, where if $$v=0$$, $$u(x)$$ is unique, otherwise $$v(x)$$ exists only when forcing is orthogonal to all trivial solutions.

if $$c=0$$,

\[ G(\theta)=B \]

\[ F(r)=C\ln r + D \]

if $$c=-\lambda^2 <0$$,

\[ G(\theta)=A\sin(\lambda\theta) + B\cos(\lambda\theta) \]

\[ F(r) = C\left(\frac{r}{R} \right)^n + D\left( \frac{r}{R} \right)^{-n}\]

\[ u(r,\theta)=B_0 + \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} F(r) G(\theta) = B_0 + \sum_{n=1}^{\infty}F(r)[A_n\sin(\lambda\theta) + B_n\cos(\lambda\theta)] \]

\[ A_n = \frac{1}{\pi}\int_0^{2\pi} f(\theta)\sin(n\theta)\,d\theta \]

\[ B_n = \frac{1}{\pi}\int_0^{2\pi} f(\theta)\cos(n\theta)\,d\theta \]

\[ B_0 = \frac{1}{2\pi}\int_0^{2\pi} f(\theta)\,d\theta \]

Wave Equation:\[ u_{tt}=c^2 u_{xx} \]

\[ u = F(x)G(t) \]

\[ \frac{F''(x)}{F(x)}=\frac{G''(t)}{G(t)}=k \text{ where } u(t,0)=F(0)=u(t,L)=F(L)=0 \]

\[ F(x) = A\sin(\lambda x) + B\cos(\lambda x) \]

\[ u_t(x,0)=g(x)=\sum_{n=1}^{\infty} A_n\lambda_n c \sin(\lambda_n x) \]

\[ A_n = \frac{2}{\lambda_n c L}\int_0^L g(y)\sin(\lambda_n y)\,dy \]

\[ G(t) = C\sin(\lambda t) + D\cos(\lambda t) \]

\[ u(x,0)=f(x)=\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}B_n\sin(\lambda_n x) \]

\[ B_n = \frac{2}{L}\int_0^L f(y)\sin(\lambda_n y)\,dy \]

\[ u(x,t)=\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}F(x)G(t)=\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}F(x)\left[C\sin(\lambda t) + D\cos(\lambda t)\right] \]

\[ \lambda_n=\frac{n\pi}{L}\text{ or }\frac{(2n+1)\pi}{2L} \]

Inhomogeneous:\[ u(0,t)=F(0)=p(t) \]

\[ u(L,t)=F(L)=q(t) \]

\[ u(x,t)=v(x,t) + \phi(x)p(t) + \psi(x)q(t) \]

Transform to forced:\[ v(x,y) = \begin{cases} v_{tt}=c^2 v_{xx} - \phi(x)p''(x) - \psi(x)q''(t) = c^2 v_{xx} + R(x,t) & \phi(x)=1 - \frac{x}{L}\;\;\;\psi(x)=\frac{x}{L}\\ v(0,t)=v(L,t)=0 & t>0 \\ v(x,0)=f(x)-\phi(x)p(0) - \psi(x)q(0) & f(x)=u(x,0) \\ v_t(x,0)=g(x)-\phi(x)p'(0) - \psi(x)q'(0) & g(x)=u_t(x,0) \end{cases} \]

Then solve as a forced equation.

Forced:\[ u_{tt}=c^2 u_{xx} + R(x,t) \]

\[ u(x,t)=u_1(x,t)+u_2(x,t) \]

$$u_1$$ found by $$R(x,t)=0$$ and solving.

\[ u_2(x,t)=\sum_{n=1}^{\infty} C_n(t)\sin\left(\frac{n\pi x}{L}\right) \]

where $$\sin\frac{n\pi x}{L}$$ are the eigenfunctions from solving $$R(x,t)=0$$

\[ R(x,t)=\sum_{n=1}^{\infty} R_n(t)\sin\left(\frac{n\pi x}{L}\right) \]

\[ R_n(t)=\frac{2}{L}\int_0^L R(y,t)\sin\left(\frac{n\pi x}{L}\right)\,dy \]

\[ C_n''(t) + k^2 C_n(t)=R_n(t) \]

\[ C_n(t)=\alpha\sin(k t) + \beta\cos(k t) + sin(k t)\int_0^t R_n(s)\cos(k s)\,ds - \cos(k t)\int_0^t R_n(s)\sin(k s)\,ds \]

where $$C_n(0)=0$$ and $$c_n'(0)=0$$

Fourier Transform:

\[ \mathcal{F}(f)=\hat{f}(k)=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}}\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} f(\xi) e^{-i k \xi}\,d\xi \]

\[ \mathcal{F}^{-1}(f)=f(x)=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}}\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \hat{f}(k) e^{ikx}\,dk \]

\[ \mathcal{F}(f+g)=\widehat{f+g}=\hat{f} + \hat{g} \]

\[ \widehat{fg}\neq\hat{f}\hat{g} \]

\[ \widehat{f'}=ik\hat{f}\text{ or }\widehat{f^{(n)}}=(ik)^n\hat{f} \]

\[ \widehat{u_t} = \frac{\partial \hat{u}}{\partial t} = \hat{u}_t \]

\[ \widehat{u_{tt}}=\frac{\partial^2\hat{u}}{\partial t^2}=\hat{u}_{tt} \]

\[ \widehat{u_{xx}}=(ik)^2\hat{u}=-k^2\hat{u} \]

\[ u(x,t)=\mathcal{F}^{-1}(\hat{u})=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \hat{f}(k) e^{\alpha^2 k^2 t} e^{ikx}\,dk \]

\[ u(x,t)=\mathcal{F}^{-1}\left(\hat{f}(k) e^{-\alpha^2 k^2 t}\right) \]

Semi-infinite:

\[ \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \hat{F}(k) e^{\alpha^2 k^2 t} e^{ikx}\,dk \]

where

\[ \hat{F}(k)=-i\sqrt{\frac{2}{\pi}}\int_0^{\infty} f(\xi)\sin(k\xi)\,d\xi \]

| $$f(x)$$ | $$\hat{f}(k)$$ |

| \[1\text{ if } -s < x < s, 0\text{ otherwise }\] | \[ \sqrt{\frac{2}{\pi}}\frac{\sin(ks)}{k} \] |

| \[ \frac{1}{x^2 + s^2} \] | \[ \frac{1}{s}\sqrt{\frac{\pi}{2}}e^{-s|k|} \] |

| \[ e^{-sx^2} \] | \[ \frac{1}{\sqrt{2s}}e^{\frac{k^2}{4s}} \] |

| \[ \frac{\sin(sx)}{x}\] | \[ \sqrt{\frac{\pi}{2}}\text{ if } |k|<s, 0\text{ otherwise} \] |

| \[ e^{isx}\text{ if } a < x < b, 0\text{ otherwise} \] | \[ \frac{i}{\sqrt{2\pi}}\left(\frac{1}{s-k} \right)\left(e^{ea(s-k)} - e^{ib(s-k)} \right) \] |

AMath 402 - Dynamical Systems and ChaosDimensionless time

\[ \tau = \frac{t}{T} \]

where T gets picked so that

\[\frac{}{}\]

and

\[\frac{}{}\]

are of order 1.

Fixed points of $$x'=f(x)$$: set $$f(x)=0$$ and solve for roots

Bifurcation: Given $$x'=f(x,r)$$, set $$f(x,r)=0$$ and solve for $$r$$, then plot $$r$$ on the $$x-axis$$ and $$x$$ on the $$y-axis$$.

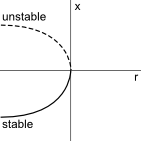

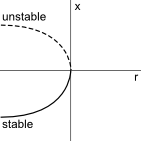

Saddle Node

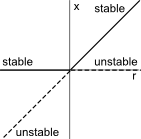

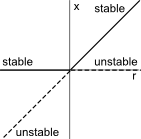

Transcritical

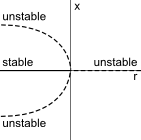

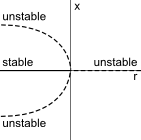

Subcritical Pitchfork

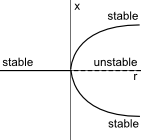

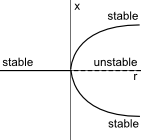

Supercritical Pitchfork

\[ \begin{matrix} x'=ax+by \\ y'=cx+dy \end{matrix} \]

\[ A=\begin{bmatrix} a & b \\ c & d \end{bmatrix}\]

\[ \begin{vmatrix} a-\lambda & b \\ c & d-\lambda \end{vmatrix}=0 \]

\[ \begin{matrix} \lambda^2 - \tau\lambda + \delta=0 & \lambda = \frac{\tau \pm \sqrt{\tau^2 - 4\delta}}{2} \\ \tau = a+d & \delta=ad-bc \end{matrix} \]

\[ x(t)=c_1 e^{\lambda_1 t}v_1 + c_2 e^{\lambda_2 t}v_2 \]

$$v_1,v_2$$ are eigenvectors.

Given $$\tau = \lambda_1 + \lambda_2$$ and $$\delta=\lambda_1\lambda_2$$:

if $$\delta < 0$$, the eigenvalues are real with opposite signs, so the fixed point is a saddle point.

otherwise, if $$\tau^2-4\delta > 0$$, its a node. This node is stable if $$\tau < 0$$ and unstable if $$\tau > 0$$

if $$\tau^2-4\delta < 0$$, its a spiral, which is stable if $$\tau < 0$$, unstable if $$\tau > 0$$, or a center if $$\tau=0$$

if $$\tau^2-4\delta = 0$$, its degenerate.

\[ \begin{bmatrix} x'=f(x,y) \\ y'=g(x,y) \end{bmatrix} \]

Fixed points are found by solving for $$x'=0$$ and $$y'=0$$ at the same time.

nullclines are when either $$x'=0$$

or $$y'=0$$ and are drawn on the phase plane.

\[ \begin{bmatrix} \frac{\partial f}{\partial x} & \frac{\partial f}{\partial y} \\ \frac{\partial g}{\partial x} & \frac{\partial g}{\partial y} \end{bmatrix} \]

$$\leftarrow$$ For nonlinear equations, evaluate this matrix at each fixed point, then use the above linear classification scheme to classify the point.

A basin for a given fixed point is the area of all trajectories that eventually terminate at that fixed point.

Given $$x'=f(x)$$, $$E(x)$$ is a conserved quantity if $$\frac{dE}{dt}=0$$

A limit cycle is an isolated closed orbit in a nonlinear system. Limit cycles can only exist in nonlinear systems.

If a function can be written as $$\vec{x}'=-\nabla V$$, then its a gradient function and can't have closed orbits.

The Liapunov function $$V(x)$$ for a fixed point $$x^*$$ satisfies $$V(x) > 0 \forall x \neq x^*, V(x^*)=0, V' < 0 \forall x \neq x^*$$

A Hopf bifurcation occurs as the fixed points eigenvalues (in terms of $$\mu$$) cross the imaginary axis.

Math 300 - Introduction to Mathematical Reasoning| P | Q | $$P \Rightarrow Q$$ | $$\neg P \vee Q$$ |

| T | T | T | T |

| T | F | F | F |

| F | T | T | T |

| F | F | T | T |

All valid values of $$x$$ constitute the Domain.$$f(x)=y$$ The range in which $$y$$ must fall is the codomain

The image is the set of $$y$$ values that are possible given all valid values of $$x$$So, $$\frac{1}{x}$$ has a domain $$\mathbb{R} - \{0\}$$ and a codomain of $$\mathbb{R}$$. However, no value of $$x$$ can ever produce $$f(x)=0$$, so the Image is $$\mathbb{R}-\{0\}$$

Injective: No two values of $$x$$ yield the same result. $$f(x_1)\neq f(x_2)$$ if $$x_1 \neq x_2$$ for all $$x$$

Surjective: All values of $$y$$ in the codomain can be produced by $$f(x)$$. In other words, the codomain equals the image.

Bijective: A Bijective function is both Injective and Surjective - all values of $$y$$ are mapped to exactly one value of $$x$$. A simple way to prove this is to solve $$f(x)$$ for $$x$$. If this can be done without creating multiple solutions (a square root, for example, yields $$\pm$$, not a single answer), then it's a bijective function.

If $$f(x)$$ is a bijection, it is denumerable. Any set that is equivalent to the natural numbers is denumerable.

$$\forall x \in \mathbb{R}$$ means "for all $$x$$ in $$\mathbb{R}$$", where $$\mathbb{R}$$ can be replaced by any set.

$$\exists y \in \mathbb{R}$$ means "there exists a $$y$$ in $$\mathbb{R}$$", where $$\mathbb{R}$$ can be replaced by any set.

\[ A \vee B = A\text{ or }B \]

\[ A \wedge B = A\text{ and }B \]

\[ P \Leftrightarrow Q\text{ means }P \Rightarrow Q \wedge Q\Rightarrow P \text{ or } P\text{ iff }Q \text{ (if and only if)} \]

$$A \cup B$$ = Union - All elements that are in either A or B, or both.

\[ \{x|x \in A \text{ or } x \in B \} \]

$$A \cap B$$ = Intersection - All elements that are in both A and B

\[ \{x|x \in A \text{ and } x \in B \} \]

$$A\subseteq B$$ = Subset - Indicates A is a subset of B, meaning that all elements in A are also in B.

\[ \{x \in A \Rightarrow x \in B \} \]

$$A \subset B$$ = Strict Subset - Same as above, but does not allow A to be equal to B (which happens if A has all the elements of B, because then they are the exact same set).

$$A-B$$ = Difference - All elements in A that aren't also in B

\[ \{x|x \in A \text{ and } x \not\in B \} \]

$$A\times B$$ = Cartesian Product - All possible ordered pairs of the elements in both sets:

\[ \{(x,y)|x \in A\text{ and }y\in B\} \]

| Proof | We use induction on $$n$$ |

| Base Case: | [Prove $$P(n_0)$$] |

| Inductive Step: | Suppose now as inductive hypothesis that [$$P(k)$$ is true] for some integer $$k$$ such that $$k \ge n_0$$. Then [deduce that $$P(k+1)$$ is true]. This proves the inductive step. |

| Conclusion: | Hence, by induction, [$$P(n)$$ is true] for all integers $$n \ge n_0$$. |

| Proof | We use strong induction on $$n$$ |

| Base Case: | [Prove $$P(n_0)$$, $$P(n_1)$$, ...] |

| Inductive Step: | Suppose now as inductive hypothesis that [$$P(n)$$ is true for all $$n \le k$$] for some positive integer $$k$$, then [deduce that $$P(k+1)$$ is true]. This proves the inductive step. |

| Conclusion: | Hence, by induction [$$P(n)$$ is true] for all positive integers $$n$$. |

| Proof: | Suppose, for contradiction, that the statement $$P$$ is false. Then, [create a contradiction]. Hence our assumption that $$P$$ is false must be false. Thus, $$P$$ is true as required. |

The composite of $$f:X\rightarrow Y$$ and $$g:Y\rightarrow Z$$ is $$g\circ f: x\rightarrow Z$$ or just $$gf: X\rightarrow Z$$. $$g\circ f = g(f(x)) \forall x \in X$$

\[ a\equiv b \bmod m \Leftrightarrow b\equiv a \bmod m \]

If

\[ a \equiv b \bmod m\text{ and }b \equiv c \bmod m,\text{ then }a \]

Negation of $$P \Rightarrow Q$$ is $$P \wedge (\neg Q)$$ or $$P and (not Q)$$

If $$m$$ is divisible by $$a$$, then $$a b_1 \equiv a b_2 \bmod m \Leftrightarrow b_1 \equiv b_2 \bmod\left(\frac{m}{a} \right)$$

Fermat's little theorem: If $$p$$ is a prime, and $$a \in \mathbb{Z}^+$$ which is not a multiple of $$p$$, then $$a^{p-1}\equiv 1 \bmod p$$.

Corollary 1: If $$p$$ is prime, then $$\forall a \in \mathbb{Z}, a^p = a \bmod p$$

Corollary 2: If $$p$$ is prime, then $$(p-1)! \equiv -1 \bmod p$$

Division theorem: $$a,b \in \mathbb{Z}$$, $$b > 0$$, then $$a = bq+r$$ where $$q,r$$ are unique integers, and $$0 \le r < b$$. Thus, for $$a=bq+r$$, $$\gcd(a,b)=\gcd(b,r)$$. Furthermore, $$b$$ divides $$a$$ if and only if $$r=0$$, and if $$b$$ divides $$a$$, $$\gcd(b,a)=b$$

Euclidean Algorithm: $$\gcd(136,96)$$

$$136=96\cdot 1 + 40$$

\[ 290x\equiv 5\bmod 357 \rightarrow 290x + 357y = 5 \]

$$96=40\cdot 2 + 16$$

\[ ax\equiv b \bmod c \rightarrow ax+cy=b \]

$$40=16\cdot 2 + 8$$

$$16=8\cdot 2 + 0 \leftarrow$$ stop here, since the remainder is now 0

$$\gcd(136,96)=8$$

Diophantine Equations (or linear combinations):

$$140m + 63n = 35$$

$$m,n \in \mathbb{Z}$$ exist for $$am+bn=c$$ iff $$\gcd(a,b)$$ divides $$c$$$$140=140\cdot 1 + 63\cdot 0$$

$$63=140\cdot 0 + 63\cdot 1$$

dividing $$am+bn=c$$ by $$\gcd(a,b)$$ always yields coprime $$m$$ and $$n$$.$$14=140\cdot 1 - 63\cdot 2$$

$$7=63\cdot 1 - 14\cdot 4 = 63 - (140\cdot 1 - 63\cdot 2)\cdot 4 = 63 - 140\cdot 4 + 63\cdot 8 = 63\cdot 9 - 140\cdot 4 $$

$$0=14 - 7\cdot 2 =140\cdot 1 - 63\cdot 2 - 2(63\cdot 9 - 140\cdot 4) = 140\cdot 9-63\cdot 20 $$

So $$m=9$$ and $$n=-20$$

Specific: $$7=63\cdot 9 - 140\cdot 4 \rightarrow 140\cdot(-4)+63\cdot 9=7\rightarrow 140\cdot(-20)+63\cdot45=35$$

So for $$140m+63n=35, m=-20, n=45$$

Homogeneous: $$140m+63n=0 \; \gcd(140,63)=7 \; 20m + 9n = 0 \rightarrow 29m=-9n$$

$$m=9q, n=-20q$$ for $$q\in \mathbb{Z}$$ or $$am+bn=0 \Leftrightarrow (m,n)=(bq,-aq)$$

General: To find

all solutions to $$140m+63n=35$$, use the specific solution $$m=-20, n=45$$

$$140(m+20) + 63(n-45) = 0$$

$$(m+20,n-45)=(9q,-20q)$$ use the homogeneous result and set them equal.

$$(m,n)=(9q-20,-20q+45)$$ So $$m=9q-20$$ and $$n=-20q+45$$

\[ [a]_m = \{x\in \mathbb{Z}| x\equiv a \bmod m \} \Rightarrow \{ mq + a|q \in \mathbb{Z} \} \]

$$ax\equiv b \bmod m$$ has a unique solution $$\pmod{m}$$ if $$a$$ and $$m$$ are coprime. If $$\gcd(a,b)=1$$, then $$a$$ and $$b$$ are coprime. $$[a]_m$$ is invertible if $$\gcd(a,m)=0$$.

Math 327 - Introduction to Real Analysis ICauchy Sequence: For all $$\epsilon > 0$$ there exists an integer $$N$$ such that if $$n,m \ge N$$, then $$|a_n-a_m|<\epsilon$$

Alternating Series: Suppose the terms of the series $$\sum u_n$$ are alternately positive and negative, that $$|u_{n+1}| \le |u_n|$$ for all $$n$$, and that $$u_n \to 0$$ as $$n\to\infty$$. Then the series $$\sum u_n$$ is convergent.

Bolzano-Weierstrass Theorem: If $$S$$ is a bounded, infinite set, then there is at least one point of accumulation of $$S$$.

$$\sum u_n$$ is absolutely convergent if $$\sum|u_n|$$ is convergent

If $$\sum u_n$$ is absolutely convergent, then $$\sum u_n = \sum a_n - \sum b_n$$ where both $$\sum a_n$$ and $$\sum b_n$$ are convergent. If $$\sum u_n$$ is conditionally convergent, both $$\sum a_n$$ and $$\sum b_n$$ are divergent.

\[ \sum u_n = U = u_0 + u_1 + u_2 + ... \]

\[ w_0 = u_0 v_0 \]

\[ w_1 = u_0 v_1 + u_1 v_0 \]

\[ \sum v_n = V = v_0 + v_1 + v_2 + ... \]

\[ w_n = u_0 v_n + u_1 v_{n-1} + ... + u_n v_0 \]

\[ \sum w_n = UV = w_0 + w_1 + w_2 + ... \]

Provided

\[ \sum u_n, \sum v_n \]

are absolutely convergent.

$$\sum a_n x^n$$ is either absolutely convergent for all $$x$$, divergent for all $$x\neq 0$$, or absolutely convergent if $$-R < x < R$$ (it may or may not converge for $$x=\pm R$$ ).

$$-R < x < R$$ is the interval of convergence. $$R$$ is the radius of convergence.

\[ R=\lim_{n \to \infty}\left|\frac{a_n}{a_{n+1}}\right| \]

if the limit exists or is $$+\infty$$

Let the functions of the sequence $$f_n(x)$$ be defined on the interval $$[a,b]$$. If for each $$\epsilon > 0$$ there is an integer $$N$$ independent of x such that $$|f_n(x) - f_m(x)| < \epsilon$$ where $$N \le m,n$$.

You can't converge uniformly on any interval containing a discontinuity.

\[ |a|+|b|\le|a+b| \]

\[ \lim_{n \to \infty}(1+\frac{k}{n})^n = e^k \]

\[ lim_{n \to \infty} n^{\frac{1}{n}}=1 \]

\[ \sum_{k=0}^{\infty}=\frac{a}{1-r} \]

if $$|r| < 1$$

\[\sum a_n x^n\]

has a radius of convergence

\[R = \lim_{n \to \infty}\left|\frac{a_n}{a_{n+1}} \right|\]

if it exists or is $$+\infty$$. The interval of convergence is $$-R < x < R$$

\[ \sum^{\infty}\frac{x^2}{(1+x^2)^n} = x^2\sum\left(\frac{1}{1+x^2}\right)^n = x^2\left(\frac{1}{1-\frac{1}{1+x^2}}\right) = x^2\left( \frac{1+x^2}{1+x^2-1}\right) = x^2\left( \frac{1+x^2}{x^2} \right) = 1+x^2 \]

Math 427 - Complex Analysis | 0 | $$\frac{\pi}{6}$$ | $$\frac{\pi}{4}$$ | $$\frac{\pi}{3}$$ | $$\frac{\pi}{2}$$ |

| $$\sin$$ | 0 | $$\frac{1}{2}$$ | $$\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}$$ | $$\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}$$ | 1 |

| $$\cos$$ | 1 | $$\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}$$ | $$\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}$$ | $$\frac{1}{2}$$ | 0 |

| $$\tan$$ | 0 | $$\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}$$ | 1 | $$\sqrt{3}$$ | $$\varnothing$$ |

\[ \frac{z_1}{z_2} = \frac{x_1 x_2 + y_1 y_2}{x_2^2 + y_2^2} + i\frac{y_1 x_1 - x_1 y_2}{x_2^2 + y_2^2} \]

\[ |z| = \sqrt{x^2 + y^2} \]

\[ \bar{z} = x-i y \]

\[ |\bar{z}|=|z| \]

\[ \text{Re}\,z=\frac{z+\bar{z}}{2} \]

\[ \text{Im}\,z=\frac{z-\bar{z}}{2i} \]

\[ \text{Arg}\,z=\theta\text{ for } -\pi < \theta < \pi \]

\[ z=re^{i\theta}=r(\cos(\theta) + i\sin(\theta)) \]

\[ \lim_{z \to z_0} f(z) = w_0 \iff \lim_{x,y \to x_0,y_0} u(x,y) = u_0 \text{ and }\lim_{x,y \to x_0,y_0} v(x,y)=v_0 \text{ where } w_0=u_0+iv_0 \text{ and } z_0=x_0+iy+0 \]

\[ \lim_{z \to z_0} f(z) = \infty \iff \lim_{z \to z_0} \frac{1}{f(z)}=0 \]

\[ \lim_{z \to \infty} f(z) = w_0 \iff \lim_{z \to 0} f\left(\frac{1}{z}\right)=w_0\]

\[ \text{Re}\,z\le |\text{Re}\,z|\le |z| \]

\[ \text{Im}\,z\le |\text{Im}\,z| \le z \]

\[ \lim_{z \to \infty} f(z) = \infty \iff \lim_{z\to 0}\frac{1}{f\left(\frac{1}{z}\right)}=0\]

\[ \left| |z_1| - |z_2| \right| \le |z_1 + z_2| \le |z_1| + |z_2| \]

Roots:

\[ z = \sqrt[n]{r_0} \exp\left[i\left(\frac{\theta_0}{n} + \frac{2k\pi}{n} \right)\right] \]

Harmonic:

\[ f_{xx} + f_{yy} = 0 \text{ or } f_{xx}=-f_{yy} \]

Cauchy-Riemann:

\[ f(z) = u(x,y)+iv(x,y) \]

\[ \sinh(z)=\frac{e^z-e^{-z}}{2}=-i\sin(iz) \]

\[ \frac{d}{dz}\sinh(z)=\cosh(z) \]

\[ u_x = v_y \]

\[ u_y = -v_x \]

\[ \cosh(z) = \frac{e^z + e^{-z}}{2} = cos(iz) \]

\[ \frac{d}{dz}\cosh(z)=\sinh(z) \]

\[ f(z) = u(r,\theta)+iv(r,\theta) \]

\[ \sin(z)=\frac{e^{iz}-e{-iz}}{2i}=i-\sinh(iz)=\sin(x)\cosh(y) + i\cos(x)\sinh(y) \]

\[ r u_r = v_{\theta} \]

\[ u_{\theta}=-r v_r \]

\[ \cos(z)=\frac{e^{iz}+e^{-iz}}{2}=\cosh(iz)=\cos(x)\cosh(y) - i \sin(x)\sinh(y) \]

\[ \sin(x)^2 + \sinh(y)^2 = 0 \]

\[ |\sin(z)|^2 = \sin(x)^2 + \sinh(y)^2 \]

\[ |\cos(z)|^2 = \cos(x)^2 + \sinh(y)^2 \]

$$e^z$$ and Log:

\[ e^z=e^{x+iy}=e^x e^{iy}=e^x(\cos(y) + i\sin(y)) \]

\[ e^x e^{iy} = \sqrt{2} e^{i\frac{\pi}{4}} \]

\[ e^x = \sqrt{2} \]

\[ y = \frac{\pi}{4} + 2k\pi \]

\[ x = \ln\sqrt{2} \]

So,

\[ z = \ln\sqrt{2} + i\pi\left(\frac{1}{4} + 2k\right) \]

\[ \frac{d}{dz} log(f(z)) = \frac{f'(z)}{f(z)} \]

Cauchy-Gourgat: If $$f(z)$$ is analytic at all points interior to and on a simple closed contour $$C$$, then

\[ \int_C f(z) \,dz=0 \]

\[ \int_C f(z) \,dz = \int_a^b f[z(t)] z'(t) \,dt \]

\[ a \le t \le b \]

$$z(t)$$ is a parameterization. Use $$e^{i\theta}$$ for circle!

Maximum Modulus Principle: If $$f(z)$$ is analytic and not constant in $$D$$, then $$|f(z)|$$ has no maximum value in $$D$$. That is, no point $$z_0$$ is in $$D$$ such that $$|f(z)| \le |f(z_0)|$$ for all $$z$$ in $$D$$.

Corollary: If $$f(z)$$ is continuous on a closed bounded region $$R$$ and analytic and not constant through the interior of $$R$$, then the maximum value of $$|f(z)|$$ in $$R$$ always exists on the boundary, never the interior.

Taylor's Theorem: Suppose $$f(z)$$ is analytic throughout a disk $$|z-z_0|<R$$. Then $$f(z)$$ has a power series of the form

\[ f(z) = \sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\frac{f^{(n)}(z_0)}{n!}(z-z_0)^n \]

where $$|z-z_0| < R_0$$ and $$n=0,1,2,...$$

Alternatively,

\[ \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} a_n(z-z_0)^n \text{ where } a_n=\frac{f^{(n)}(z_0)}{n!} \]

For $$|z|<\infty$$:

\[ e^z = \sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\frac{z^n}{n!} \]

\[ \sin(z) = \sum_{n=0}^{\infty}(-1)^n\frac{z^{2n+1}}{(2n+1)!} \]

\[ \cos(z) = \sum_{n=0}^{\infty}(-1)^n\frac{z^{2n}}{(2n)!} \]

Note that

\[ \frac{1}{1 - \frac{1}{z}}=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\left(\frac{1}{z}\right)^n \text{ for } \left|\frac{1}{z}\right| < 1\]

, which is really $$1 < |z|$$ or $$|z| > 1$$

For $$|z| < 1$$:

\[ \frac{1}{1-z} = \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} z^n \]

\[ \frac{1}{1+z} = \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} (-1)^n z^n \]

For $$|z-1|<1$$:

\[ \frac{1}{z} = \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} (-1)^n (z-1)^n \]

Analytic: $$f(z)$$ is analytic at point $$z_0$$ if it has a derivative at each point in some neighborhood of $$z_0$$.

$$f(z)=u(x,y)+iv(x,y)$$ is analytic if and only if $$v$$ is a harmonic conjugate of $$u$$.

If $$u(x,y)$$ and $$v(x,y)$$ are harmonic functions such that $$u_{xx}=-u{yy}$$ and $$v_{xx}=-v_{yy}$$, and they satisfy the Cauchy-Reimann conditions, then $$v$$ is a harmonic conjugate of $$u$$.

Differentiable: $$f(z)=u(x,y)+iv(x,y)$$ is differentiable at a point $$z_0$$ if $$f(z)$$ is defined within some neighborhood of $$z_0=x_0+iy_0$$, $$u_x$$ $$u_y$$ $$v_x$$ and $$v_y$$ exist everywhere in the neighborhood, those first-order partial derivatives exist at $$(x_0,y_0)$$ and satisfy the Reimann-Cauchy conditions at $$(x_0,y_0)$$.

Cauchy Integral Formula:

\[ \int_C \frac{f(z)}{z-z_0}\,dz = 2\pi i f(z_0) \]

where $$z_0$$ is any point interior to $$C$$ and $$f(z)$$ is analytic everywhere inside and on $$C$$ taken in the positive sense. Note that $$f(z)$$ here refers to the actual function $$f(z)$$,

not $$\frac{f(z)}{z-z_0}$$

Generalized Cauchy Integral Formula:

\[ \int_C \frac{f(z)}{(z-z_0)^{n+1}}\,dz = \frac{2\pi i}{n!} f^{(n)}(z_0) \]

(same conditions as above)

Remember, discontinuities that are roots can be calculated and factored:

\[ \frac{1}{z^2-w_0}=\frac{1}{(z-z_1)(z-z_2)} \]

Residue at infinity:

\[ \int_C f(z)\,dz = 2\pi i \,\mathop{Res}\limits_{z=0}\left[\frac{1}{z^2} f\left(\frac{1}{z}\right) \right] \]

A residue at $$z_0$$ is the $$n=-1$$ term of the Laurent series centered at $$z_0$$.

A point $$z_0$$ is an isolated singular point if $$f(z_0)$$ fails to be analytic, but is analytic at some point in every neighborhood of $$z_0$$, and there's a deleted neighborhood $$0 < |z-z_0| < \epsilon$$ of $$z_0$$ throughout which $$f$$ is analytic.

\[ \mathop{Res}\limits_{z=z_0}\,f(z)=\frac{p(z_0)}{q'(z_0)}\text{ where }f(z) = \frac{p(z)}{q(z)}\text{ and } p(z_0)\neq 0 \]

\[ \int_C f(z)\,dz = 2\pi i \sum_{k=1}^n\,\mathop{Res}\limits_{z=z_k}\,f(z) \]

where $$z_0$$, $$z_1$$, $$z_2$$,... $$z_k$$ are all the singular points of $$f(z)$$ (which includes poles).

If a series has a finite number of $$(z-z_0)^{-n}$$ terms, its a pole ($$\frac{1}{z^4}$$ is a pole of order 3). If a function, when put into a series, has

no $$z^{-n}$$ terms, it's a removable singularity. If it has an infinite number of $$z^{-n}$$ terms, its an essential singularity (meaning, you can't get rid of it).

AMath 401 - Vector Calculus and Complex Variables$$||\vec{x}||=\sqrt{x_1^2+x_2^2+ ...}$$

$$\vec{u}\cdot\vec{v} = ||\vec{u}||\cdot||\vec{v}|| \cos(\theta)=u_1v_1+u_2v_2+ ...$$

$$||\vec{u}\times\vec{v}|| = ||\vec{u}||\cdot||\vec{v}|| \sin(\theta) = \text{ area of a parallelogram}$$

\[ \vec{u}\times\vec{v} = \begin{vmatrix} \vec{\imath} & \vec{\jmath} & \vec{k} \\ u_1 & u_2 & u_3 \\ v_1 & v_2 & v_3 \end{vmatrix} \]

\[ \begin{vmatrix} a & b \\ c & d \end{vmatrix} = ad-bc \]

\[ \vec{u}\cdot\vec{v}\times\vec{w} = \vec{u}\cdot(\vec{v}\times\vec{w})=\text{ volume of a parallelepiped} \]

\[ h_?\equiv\left|\left|\frac{\partial\vec{r}}{\partial ?}\right|\right| \]

\[ \hat{e}_r(\theta)=\frac{1}{h_r}\frac{\partial\vec{r}}{\partial r} \]

\[ \hat{e}_r'(\theta)=\frac{d\hat{e}_r}{d\theta}=\hat{e}_{\theta}(\theta) \]

\[ \vec{r}=r(t)\hat{e}_r(\theta(t)) \]

\[ \vec{r}'(t)=r'(t)\hat{e}_r + r(t)\frac{d\hat{e}_r}{dt}\]

\[ \vec{r}'(t)=r'(t)\hat{e}_r + r(t)\frac{d\hat{e}_r}{d\theta}\frac{d\theta}{dt}=r'(t)\hat{e}_r + r(t)\hat{e}_{\theta} \theta'(t) \]

Projection of $$\vec{u}$$ onto $$\vec{v}$$:

\[ ||\vec{u}|| \cos(\theta) = \frac{\vec{u}\cdot\vec{v}}{||\vec{v}||} \]

Arc Length:

\[ \int_a^b \left|\left| \frac{d\vec{r}}{dt} \right|\right| \,dt = \int_a^b ds \]

Parametrization:

\[ s(t) = \int_a^t \left|\left|\frac{d\vec{r}}{dt}\right|\right| \,dt \]

\[ \frac{dx}{dt}=x'(t) \]

\[ dx = x'(t)\,dt \]

\[ \oint x \,dy - y \,dx = \oint\left(x \frac{dy}{dt} - y \frac{dx}{dt}\right)\,dt = \oint x y'(t) - y x'(t) \,dt \]

\[ \nabla = \frac{\partial}{\partial x}\vec{\imath} + \frac{\partial}{\partial y}\vec{\jmath} + \frac{\partial}{\partial z}\vec{k} \]

\[ \nabla f = \left\langle \frac{\partial f}{\partial x},\frac{\partial f}{\partial y},\frac{\partial f}{\partial z} \right\rangle \]

\[ D_{\vec{u}} f(\vec{P})=f'_{\vec{u}}=\nabla f \cdot \vec{u} \]

\[ \nabla(fg)=f\nabla g + g \nabla f \]

\[ \vec{F}(x,y,z)=F_1(x,y,z)\vec{\imath} + F_2(x,y,z)\vec{\jmath} + F_3(x,y,z)\vec{k} \]

\[ \text{div}\, \vec{F} = \nabla \cdot \vec{F} = \frac{\partial F_1}{\partial x} + \frac{\partial F_2}{\partial y} + \frac{\partial F_3}{\partial z} \]

\[ \text{curl}\, \vec{F} = \nabla \times \vec{F} = \left\langle \frac{\partial F_3}{\partial y} - \frac{\partial F_2}{\partial z}, \frac{\partial F_1}{\partial z} - \frac{\partial F_3}{\partial x}, \frac{\partial F_2}{\partial x} - \frac{\partial F_1}{\partial y} \right\rangle \]

Line integral:

\[ \int_{\vec{r}(a)}^{\vec{r}(b)}\vec{F}\cdot \vec{r}'(t)\,dt = \int_{\vec{r}(a)}^{\vec{r}(b)}\vec{F}\cdot d\vec{r} \]

Closed path:

\[ \oint \vec{F}\cdot d\vec{r} \]

\[ d\vec{r} = \nabla\vec{r}\cdot \langle du_1,du_2,du_3 \rangle = h_1 du_1 \hat{e}_1 + h_2 du_2 \hat{e}_2 + h_3 du_3 \hat{e}_3 \]

\[ h_?= \left|\left| \frac{\partial\vec{r}}{\partial ?} \right|\right| = \frac{1}{||\partial ?||} \]

\[ \hat{e}_?=\frac{1}{h_?}\frac{\partial\vec{r}}{\partial?}=h_?\nabla?(x,y,z)=\frac{\nabla?}{||\nabla?||} \]

If $$\vec{r}=\vec{r}(s)$$ then

\[ \int_a^b\vec{F}\cdot \frac{d\vec{r}}{ds} \,ds = \int_a^b\vec{F}\cdot\vec{T} \,ds\]

\[ \nabla f \cdot \hat{e}_?=\frac{1}{h_?}\frac{\partial f}{\partial ?} \]

\[ \nabla f = (\nabla f \cdot \hat{e}_r)\hat{e}_r + (\nabla f \cdot \hat{e}_{\theta})\hat{e}_{\theta} = \frac{\partial f}{\partial r}\hat{e}_r + \frac{1}{r}\frac{\partial f}{\partial \theta}\hat{e}_{\theta} \]

\[ ds = \sqrt{d\vec{r}\cdot d\vec{r}} = \left|\left| \frac{d\vec{r}}{dt}dt \right|\right| = \sqrt{h_1^2 du_1^2 + h_2^2 du_2^2+h_3^2 du_3^2} \]

\[ Spherical: h_r=1, h_{\theta}=r, h_{\phi}=r\sin(\theta) \]

\[ \vec{r}=\frac{\nabla f}{||\nabla f||} \]

\[ \vec{r}=\vec{r}(u,v) \]

\[ \vec{n}= \frac{\frac{\partial\vec{r}}{\partial u}\times\frac{\partial\vec{r}}{\partial v}}{\left|\left| \frac{\partial\vec{r}}{\partial u}\times\frac{\partial\vec{r}}{\partial v} \right|\right|} \]

$$\vec{F}$$ is conservative if:

\[ \vec{F}=\nabla\phi \]

\[ \nabla\times\vec{F}=0 \]

\[ \vec{F}=\nabla\phi \iff \nabla\times\vec{F}=0 \]

\[ \iint\vec{F}\cdot d\vec{S} \]

\[ d\vec{S}=\left(\frac{\partial\vec{r}}{\partial u} \times \frac{\partial\vec{r}}{\partial v} \right)\,du\,dv \]

\[ d\vec{S}=\vec{n}\,dS \]

Surface Area:

\[ \iint \,dS \]

Flux:

\[ \iint\vec{F}\cdot d\vec{S} \]

Shell mass:

\[ \iint p\cdot dS \]

Stokes:

\[ \iint(\nabla\times\vec{F})\cdot d\vec{S} = \oint\vec{F}\cdot d\vec{r} \]

Divergence:

\[ \iiint\limits_V\nabla\cdot\vec{F}\,dV=\iint\limits_{\partial v} \vec{F}\cdot d\vec{S} \]

If $$z=f(x,y)$$, then

\[ \vec{r}(x,y) = \langle x,y,f(x,y) \rangle \]

\[ \nabla\cdot\vec{F}=\frac{1}{h_1 h_2 h_3}\left[\frac{\partial}{\partial u_1}(F_1 h_2 h_3) + \frac{\partial}{\partial u_2}(F_2 h_1 h_3) + \frac{\partial}{\partial u_3}(F_3 h_1 h_2) \right] \]

\[ dV = \left| \frac{\partial\vec{r}}{\partial u_1}\cdot\left(\frac{\partial\vec{r}}{\partial u_2}\times\frac{\partial\vec{r}}{\partial u_3} \right) \right| du_1 du_2 du_3 \]

If orthogonal,

\[ I = \iiint\limits_V f(u_1,u_2,u_3)h_1 h_2 h_3\,du_1\,du_2\,du_3 \]

\[ (x-c_x)^2 + (y-c_y)^2 = r^2 \Rightarrow \vec{r}(t)=\langle c_x + r\cos(t),c_y+r\sin(t) \rangle \]

Ellipse:

\[ \Rightarrow \vec{r}(t)=\langle c_x+a\cos(t), c_y+b\sin(t) \rangle \]

For spherical, if $$\theta$$ is innermost, its max value is $$\pi$$, or if its on the z value.

\[ \vec{r}(\theta,\phi)=\langle \sin(\theta)\cos(\phi), \sin(\theta)\sin(\phi),\cos(\theta) \rangle \]

Laplace Transform:

\[ \mathcal{L}\left[f(t)\right]=F(s)=\int_0^{\infty}e^{-st}f(t)\,dt \]

\[ \mathcal{L}[f'(t)] = s\mathcal{L}[f(t)] - f(0) = s\cdot F(s)-f(0)\]

\[ \mathcal{L}[f''(t)] = s^2\mathcal{L}[f(t)] - s\cdot f(0) - f'(0) = s^2\cdot F(s) - s\cdot f(0) - f'(0)\]

\[ \mathcal{L}[0] = 0 \]

\[ \mathcal{L}[1] = \frac{1}{s} \]

\[ \mathcal{L}[k] = \frac{k}{s} \]

\[ \mathcal{L}[e^{at}] = \frac{1}{s-a} \]

\[ \mathcal{L}[\cos(\omega t)] = \frac{s}{s^2 + \omega^2} \]

\[ \mathcal{L}[\sin(\omega t)] = \frac{\omega}{s^2 + \omega^2} \]

Math 461 - Combinatorial Theory IGeneral Pigeon: Let $$n$$,$$m$$, and $$r$$ be positive integers so that $$n>rm$$. Let us distribute $$n$$ balls into $$m$$ boxes. Then there will be at least 1 box in which we place at least $$r+1$$ balls.

| Base Case: | Prove $$P(0)$$ or $$P(1)$$ |

| Inductive Step: | Show that by assuming the inductive hypothesis $$P(k)$$, this implies that $$P(k+1)$$ must be true. |

| Strong Induction: | Show that $$P(k+1)$$ is true if $$P(n)$$ for all $$n < k+1$$ is true. |

There are $$n!$$ permutations of an $$n$$-element set (or $$n!$$ linear orderings of $$n$$ objects)

$$n$$ objects sorted into $$a,b,c,...$$ groups have $$\frac{n!}{a!b!c!...}$$ permutations. This is also known as a $$k$$-element multiset of $$n$$.

Number of $$k$$-digit strings in an $$n$$-element alphabet: $$n^k$$. All subsets of an $$n$$-element set: $$2^n$$

Let $$n$$ and $$k$$ be positive integers such that $$n \ge k$$, then the number of $$k$$-digit strings over an $$n$$-element alphabet where no letter is used more than once is $$\frac{n!}{(n-k)!}=(n)_k$$

\[ \binom{n}{k} = \frac{n!}{k!(n-k)!} = \frac{(n)_k}{k!} \rightarrow \]

This is the number of $$k$$-element subsets in $$[n]$$, where $$[n]$$ is an $$n$$-element set.

\[ \binom{n}{k} = \binom{n}{n-k} \]

\[ \binom{n}{0} = \binom{n}{n} = \binom{0}{0} = 1 \]

Number of $$k$$-element multisets in $$[n]$$:

\[ \binom{n+k-1}{k} \]

Binomial Theorem:

\[ (x+y)^n = \sum_{k=0}^n\binom{n}{k}x^k y^{n-k} \text{ for } n \ge 0 \]

Multinomial Theorem:

\[ (x_1 + x_2 + ... + x_k)^n = \sum_{a_1,a_2,...,a_k} \binom{n}{a_1,a_2,...,a_k} x_1^{a_1} x_2^{a_2} ... x_k^{a_k} \]

\[ \binom{n}{k} + \binom{n}{k+1} = \binom{n+1}{k+1} \text{ for } n,k \ge 0 \]

\[ \binom{k}{k} + \binom{k+1}{k} + ... + \binom{n}{k} = \binom{n+1}{k+1} \text{ for } n,k \ge 0 \]

\[ \binom{n}{k} \le \binom{n}{k} \text{ if and only if } k \le \frac{n-1}{2} \text{ and } n=2k+1 \]

\[ \binom{n}{k} \ge \binom{n}{k} \text{ if and only if } k \ge \frac{n-1}{2} \text{ and } n=2k+1 \]

\[ \binom{n}{a_1,a_2,...,a_k} = \frac{n!}{a_1!a_2!...a_k!} \]

\[ \binom{n}{a_1,a_2,...,a_k} = \binom{n}{a_1}\cdot \binom{n-a_1}{a_2} \cdot ... \cdot \binom{n-a_1-a_2-...-a_{k-1}}{a_k} \text{ if and only if } n=\sum_{i=1}^k a_i\]

\[ \binom{m}{k} = \frac{m(m-1)...(m-k+1)}{k!} \text{ for any real number } m \]

\[ (1+x)^m = \sum_{n\ge 0}^{\infty} \binom{m}{n}x^n \]

\[ \sum_{k=0}^n (-1)^k\binom{n}{k} = 0 \text{ for } n \ge 0 \]

\[ 2^n = \sum_{k=0}^n \binom{n}{k} = 0 \text{ for } n \ge 0 \]

\[ \sum_{k=1}^n k\binom{n}{k} = n 2^{n-1} \text{ for } n \ge 0 \]

\[ \binom{n+m}{k} = \sum_{i=0}^k \binom{n}{i} \binom{n}{k-i} \text{ for } n,m,k \ge 0 \]

\[ |E| = \frac{1}{2}\sum_{v\in V} deg(v) \]

or, the number of edges in a graph is half the sum of its vertex degrees.

| Compositions: | $$n$$ identical objects

$$k$$ distinct boxes | \[\binom{n-1}{k-1}\] | $$n$$ identical objects

any number of distinct boxes | $$2^{n-1}$$ |

Weak Compositions:

(empty boxes allowed) | $$n$$ identical objects

$$k$$ distinct boxes | \[ \binom{n+k-1}{k-1} \] | $$n$$ distinct objects

$$k$$ distinct boxes | $$k^n$$ |

Split $$n$$ people into $$k$$ groups of $$\frac{n}{k}$$:

Unordered:

\[ \frac{n!}{\left(\left(\frac{n}{k}\right)!\right)^k k!} \]

Ordered:

\[ \frac{n!}{\left(\left(\frac{n}{k}\right)!\right)^k} \]

Steps from (0,0) to (n,k) on a lattice:

\[\binom{n+k}{k}\]

Ways to roll $$n$$ dice so all numbers 1-6 show up at least once: $$6^n - \binom{6}{5}5^n + \binom{6}{4}4^n + \binom{6}{3}3^n + \binom{6}{2}2^n + \binom{6}{1}$$

The Sieve: $$|A_1| + |A_2| - |A_1\cap A_2|$$ or $$|A_1| + |A_2| + |A_3| - |A_1\cap A_2| - |A_1\cap A_3| - |A_2\cap A_3| + |A_1\cap A_2\cap A_3|$$

Also, $$|S - (S_A\cap S_B\cap S_C)| = |S| - |S_A| - |S_B| - |S_C| + |S_A\cap S_B| + |S_A\cap S_C| + |S_B\cap S_C| - |S_A\cap S_B\cap S_C|$$

Graphs: A

simple graph has no loops (edges connecting a vertex to itself) or multiple edges between the same vertices. A

walk is a path through a series of connected edges. A

trail is a walk where no edge is traveled on more than once. A

closed trail starts and stops on the same vertex. A

Eulerian trail uses all edges in a graph. A trail that doesn't touch a vertex more than once is a

path. $$K_n$$ is the complete graph on $$n$$-vertices.

If one can reach any vertex from any other on a graph $$G$$, then $$G$$ is a

connected graph.

A connected graph has a closed Eulerian trail if and only if all its vertices have even degree. Otherwise, it has a Eulerian trail starting on S and ending on T if only S and T have odd degree.

In a graph without loops there are an even number of vertices of odd-degree. A cycle touches all vertices only once, except for the vertex it starts and ends on. A Hamiltonian cycle touches all vertices on a graph.

Let $$G$$ be a graph on $$n \ge 3$$ vertices, then $$G$$ has a Hamiltonian cycle if all vertices in $$G$$ have degree equal or greater than $$n/2$$. A complete graph $$K_n$$ has $$\binom{n}{k}\frac{(k-1)!}{2}$$ cycles of $$k$$-vertices.

Total Cycles:

\[ \sum_{k=3}^n\binom{n}{k}\frac{(k-1)!}{2} \]

Hamiltonian cycles:

\[ \frac{(n-1)!}{2} \]

Two graphs are the same if for any pair of vertices, the number of edges connecting them is the same in both graphs. If this holds when they are unlabeled, they are isomorphic.

A Tree is a minimally connected graph: Removing any edge yields a disconnected graph. Trees have no cycles, so any connected graph with no cycles is a tree.

All trees on $$n$$ vertices have $$n-1$$ edges, so any connected graph with $$n-1$$ edges is a tree.

Let $$T$$ be a tree on $$n \ge 2$$ vertices, then T has at least two vertices of degree 1.

Let $$F$$ be a forest on $$n$$ vertices with $$k$$ trees. Then F has $$n-k$$ edges.

Cayley's formula: The number of all trees with vertex set $$[n]$$ is $$A_n = n^{n-2}$$

A connected graph $$G$$ can be drawn on a plane so that no two edges intersect, then G is a planar graph.

A connected planar graph or convex polyhedron satisfies: Vertices + Faces = Edges + 2

$$K_{3,3}$$ and $$K_5$$ are not planar, nor is any graph with a subgraph that is edge-equivalent to them.

A convex Polyhedron with V vertices, E edges, and F faces satisfies: $$3F \le 3E$$, $$3V \le 3E$$, $$E \le 3V-6$$, $$E \le 3F-6$$, one face has at most 5 edges, and one vertex has at most degree 5.

$$K_{3,3}$$ has 6 vertices and 9 edges

A graph on $$n$$-vertices has $$\binom{n}{2}$$ possible edges.

If a graph is planar, then $$E \le 3V - 6$$. However, some non-planar graphs, like $$K_{3,3}$$, satisfy this too.

Prüfer code: Remove the smallest vertex from the graph, write down only its neighbor's value, repeat.

Math 462 - Combinatorial Theory IIAll labeled graphs on $$n$$ vertices:

\[ 2^{\binom{n}{2}} \]

There are $$(n-1)!$$ ways to arrange $$n$$ elements in a cycle.

Given $$h_n=3 h_{n-1} - 2 h_{n-2}$$, change to $$h_{n+2}=3 h_{n+1} - 2 h_n$$, then $$h_{n+2}$$ is $$n=2$$ so multiply by $$x^{n+2}$$

\[ \sum h_{n+2}x^{n+2} = 3 \sum h_{n+1}x^{n+2} - 2 \sum h_n x^{n+2} \]

Then normalize to

\[ \sum_{n=2}^{\infty}h_n x^n \]

by subtracting $$h_0$$ and $$h_1$$

\[ \sum h_n x^n - x h_1 - h_0 = 3 x \sum h_{n+1}x^{n+1} - 2 x^2 \sum h_n x^n \]

\[ G(x) - x h_1 - h_0 = 3 x (G(x)-h_0) - 2 x^2 G(x) \]

Solve for:

\[ G(x) = \frac{1-x}{2x^2-3x+1} = \frac{1}{1-2x} = \sum (2x)^n \]

\[ G(x) = \sum(2x)^n = \sum 2^n x^n = \sum h_n x^n \rightarrow h_n=2^n \]

\[ \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \frac{x^n}{n!} = e^x \]

\[ \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} (cx)^n = \frac{1}{1-cx} \]

Also,

\[ 2e_1 + 5e_2 = n \rightarrow \sum h_n x^n = \sum x^{2e_1+5e_2} = \sum x^{2e_1} x^{5e_2} = \left(\sum^{\infty} x^{2e_1}\right)\left(\sum^{\infty} x^{5e_2}\right)=\frac{1}{(1-x^2)(1-x^5)}\]

$$S(n,k)$$: A Stirling number of the second kind is the number of nonempty partitions of $$[n]$$ into k blocks where the order of the blocks doesn't matter. $$S(n,k)=S(n-1,k-1)+k S(n-1,k)$$, $$S(n,n-2) = \binom{n}{3} + \frac{1}{2}\binom{k}{2}\binom{n+2}{2}$$

Bell Numbers:

\[ B(n) = \sum_{i=0}^n S(n,i) \]

, or the number of all partitions of $$[n]$$ into nonempty parts (order doesn't matter).

Catalan Number $$C_n$$:

\[ \frac{1}{n+1}\binom{2n}{n} \]

derived from

\[ \sum_{n \ge 1} c_{n-1} x^n = x C(x) \rightarrow C(x) - 1 = x C(x)\cdot C(x) \rightarrow C(x) = \frac{1 - \sqrt{1-4x}}{2x} \]

Products: Let $$A(n) = \sum a_n x^n$$ and $$B(n) = \sum b_n x^n$$. Then $$A(x)B(x)=C(x)=\sum c_n x^n$$ where

\[ c_n = \sum_{i=0}^n a_i b_{n-i} \]

Cycles: The number of $$n$$-permuatations with $$a_i$$ cycles of length $$i \in [n]$$ is \frac{n!}{a_1!a_2!...a_n!1^{a_1}2^{a_2}...n^{a_n}}

The number of n-permutations with only one cycle is $$(n-1)!$$

$$c(n,k)$$: The number of $$n$$-permutations with $$k$$-cycles is called a signless stirling number of the first kind.

$$c(n,k) = c(n-1,k-1) + (n-1) c(n-1,k)$$

\[ c(n,n-2)= 2\binom{n}{3} + \frac{1}{2}\binom{n}{2}\binom{n-2}{2} \]

$$s(n,k) = (-1)^{n-k} c(n,k)$$ and is called a signed stirling number of the first kind.

Let $$i \in [n]$$, then fro all $$k \in [n]$$, there are $$(n-1)!$$ permutations that contain $$i$$ in a $$k$$-cycle.

\[ T(n,k)=\frac{k-1}{2k}n^2 - \frac{r(k-r)}{2k} \]

Let Graph $$G$$ have $$n$$ vertices and more than $$T(n,k)$$ edges. Then $$G$$ contains a $$K_{k+1}$$ subgraph, and is therefore not $$k$$-colorable.

$$N(T)$$ = all neighbors of the set of vertices $$T$$

$$a_{s,d} = \{ s,s+d,s+2d,...,s+(n-1)d \}$$

$$\chi(H)$$: Chromatic number of Graph $$H$$, or the smallest integer $$k$$ for which $$H$$ is $$k$$-colorable.

A 2-colorable graph is bipartite and can divide its vertices into two disjoint sets.

A graph is bipartite if and only if it does not contain a cycle of odd length.

A bipartite graph has at most $$\frac{n^2}{4}$$ edges if $$n$$ is even, and at most $$\frac{n^2 - 1}{4}$$ edges if $$n$$ is odd.

If graph $$G$$ is not an odd cycle nor complete, then $$\chi(G) \le$$ the largest vertex degree $$\ge 3$$.

A bipartite graph on $$n$$ vertices with a max degree of $$k$$ has at most $$k\cdot (n-k)$$ edges.

A tree is always bipartite (2-colorable).

Philip Hall's Theorem: Let a bipartite graph $$G=(X,Y)$$. Then $$X$$ has a perfect matching to $$Y$$ if and only if for all $$T \subset X, |T| \le |N(T)|$$

$$R(k,l):$$ The Ramsey Number $$R(k,l)$$ is the smallest integer such that any 2-coloring of a complete graph on $$R(k,l)$$ vertices will contain a red $$k$$-clique or blue $$l$$-clique. A $$k$$-clique is a complete subgraph on $$k$$ vertices.

\[ R(k,l) \le R(k,l-1) + R(k-1,l) \]

\[ R(k,k) \le 4^{k-1} \]

\[ R(k,l) \le \binom{k+l-2}{l-1} \]

Let $$P$$ be a partially ordered set (a "poset"), then:

1) $$\le$$ is reflexive, so $$x \le x$$ for all $$x \in P$$

2) $$\le$$ is transitive, so that if $$x \le y$$ and $$y \le z$$ then $$x \le z$$

3) $$\le$$ is anti-symmetric, such that if $$x\le y$$ and $$y \le x$$, then $$x=y$$

Let $$P$$ be the set of all subsets of $$[n]$$, and let $$A \le B$$ if $$A \subset B$$. Then this forms a partially ordered set $$B_n$$, or a Boolean Algebra of degree $$n$$.

\[ E(X)=\sum_{i \in S} i\cdot P(X=i) \]

A chain is a set with no two incomparable elements. An antichain has no comparable elements.

Real numbers are a chain. $$\{ (2,3), (1,3), (3,4), (2,4) \}$$ is an antichain in $$B_4$$, since no set contains another.

Dilworth: In a finite partially ordered set $$P$$, the size of any maximum antichain is equal to the number of chains in any chain cover.

Weak composition of n into 4 parts: $$a_1 + a_2 + a_3 + a_4 = n$$

Applying these rules to the above equation: $$a_1 \le 2, a_2\text{ mod }2 \equiv 0, a_3\text{ mod }2 \equiv 1, a_3 \le 7, a_4 \ge 1$$

Yields the following:

\[ a_1 + 2a_2 + (2a_3 + 1) + a_4 = n \]

\[(\sum_0^2 x^{a_1})(\sum_0^{\infty} x^{2a_2})(\sum_0^3 x^{2a_3 + 1})(\sum_1^{\infty} x^{a_4})=\frac{1+x+x^2}{1-x^2}(x+x^3+x^5+x^7)\left(\frac{1}{1-x} - 1\right)\]

Math 394 - Probability Iboth E and F:

\[ P(EF) = P(E\cap F) \]

If E and F are independent, then

\[ P(E\cap F) = P(E)P(F) \]

$$P(F) = P(E) + P(E^c F)$$ $$P(E\cup F) = P(E) + P(F) - P(EF)$$

$$P(E\cup F \cup G) = P(E) + P(F) + P(G) - P(EF) - P(EG) - P(FG) + P(EFG)$$

E occurs given F:

\[P(E|F)=\frac{P(EF)}{P(F)} \]

$$P(EF)=P(FE)=P(E)P(F|E)$$

Bayes formula:

\[ P(E)=P(EF)+P(EF^c) \]

\[P(E)=P(E|F)P(F) + P(E|F^c)P(F^c) \]

\[P(E)=P(E|F)P(F) + P(E|F^c)[1 - P(F)] \]

\[ P(B|A)=P(A|B)\frac{P(B)}{P(A)} \]

The odds of A:

\[ \frac{P(A)}{P(A^c)} = \frac{P(A)}{1-P(A)} \]

\[P[\text{Exactly } k \text{ successes}]=\binom{n}{k}p^k(1-p)^{n-k} \]

\[ P(n \text{ successes followed by } m \text{ failures}) = \frac{p^{n-1}(1-q^m)}{p^{n-1}+q^{m-1}-p^{n-1}q^{m-1}} \]

where $$p$$ is the probability of success, and $$q=1-p$$ for failure.

\[ \sum_{i=1}^{\infty}p(x_i)=1 \]

where $$x_i$$ is the $$i^{\text{th}}$$ value that $$X$$ can take on.

\[ E[X] = \sum_{x:p(x) > 0}x p(x) \text{ or }\sum_{i=1}^{\infty} x_i p(x_i) \]

\[ E[g(x)]=\sum_i g(x_i)p(x_i) \]

\[ E[X^2] = \sum_i x_i^2 p(x_i) \]

\[ Var(X) = E[X^2] - (E[X])^2 \]

\[ Var(aX+b) = a^2 Var(X) \]

for constant $$a,b$$

\[ SD(X) = \sqrt{Var(X)} \]

Binomial random variable $$(n,p)$$:

\[ p(i)=\binom{n}{i}p^i(1-p)^{n-i}\; i=0,1,...,n\]

where $$p$$ is the probability of success and $$n$$ is the number of trials.

Poisson:

\[ E[X] = np \]

\[ E[X^2] = \lambda(\lambda + 1) \]

\[ Var(X)=\lambda \]

\[ P[N(t)=k)] = e^{-\lambda t}\frac{(\lambda t)^k}{k!} \: k=0,1,2,... \]

where $$N(t)=[s,s+t]$$

\[ E[X] = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} x f(x) \,dx \]

\[ P\{X \le a \} = F(a) = \int_{-\infty}^a f(x) \,dx \]

\[ \frac{d}{da} F(g(a))=g'(a)f(g(a))\]

\[ E[g(X)]=\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} g(x) f(x) \,dx \]

\[ P\{ a \le X \le b \} = \int_a^b f(x) \,dx \]

Uniform:

\[ f(x) = \frac{1}{b-a} \text{ for } a\le x \le b \]

\[ E[X] = \frac{a+b}{2} \]

\[ Var(X) = \frac{(b-a)^2}{12}\]

Normal:

\[ f(x) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi} \sigma} e^{-\frac{(x-\mu)^2}{2\sigma^2}} \text{ for } -\infty \le x \le \infty \]

\[ E[X] = \mu \]

\[ Var(X) = \sigma^2 \]

\[ Z = \frac{X-\mu}{\sigma} \]

\[ P\left[a \le X \le b\right] = P\left[ \frac{a - \mu}{\sigma} < \frac{X - \mu}{\sigma} < \frac{b - \mu}{\sigma}\right] = \phi\left(\frac{b-\mu}{\sigma}\right) - \phi\left(\frac{a-\mu}{\sigma}\right) \]

\[ \phi(x) = GRAPH \]

\[ P[X \le a]=\phi\left(\frac{a-\mu}{\sigma}\right) \]

\[ P[Z > x] = P[Z \le -x] \]

\[ \phi(-x)=1-\phi(x) \]

\[ Y=f(X) \]

\[ F_Y=P[Y\le a]= P[f(X) \le a] = P[X \le f^{-1}(a)]=F_x(f^{-1}(a)) \]

\[ f_Y=\frac{d}{da}(f^{-1}(a))f_x(f^{-1}(a)) \]

\[ Y = X^2 \]

\[ F_Y = P[Y \le a] = P[X^2 \le a] = P[-\sqrt{a} \le X \le \sqrt{a}] = \int_{-\sqrt{a}}^{\sqrt{a}} f_X(x) dx \]

\[ f_Y = \frac{d}{da}(F_Y) \]

\[N(k) \ge x \rightarrow 1 - N(k) < x \]

\[ P(A \cap N(k) \ge x) = P(A) - P(A \cap N(k) < x) \]

Discrete:

\[ P(X=1) = P(X \le 1) - P(X < 1) \]

Continuous:

\[ P(X \le 1) = P(X < 1) \]

Exponential:

\[ f(x) = \lambda e^{-\lambda x} \text{ for } x \ge 0 \]

\[ E[X] = \frac{1}{\lambda} \]

\[ Var(X) = \frac{1}{\lambda^2} \]

Gamma:

\[ f(x) = \frac{\lambda e^{-\lambda x} (\lambda x)^{\alpha - 1}}{\Gamma(\alpha)} \]

\[ \Gamma(\alpha)=\int_0^{\infty} e^{-x}x^{\alpha-1} \,dx \]

\[ E[X] = \frac{\alpha}{\lambda} \]

\[ Var(X) = \frac{\alpha}{\lambda^2} \]

\[ E[X_iX_j] = P(X_i = k \cap X_j=k) = P(X_i = k)P(X_j = k|X_i=k) \]

Stat 390 - Probability and Statistics for Engineers and Scientists\[ p(x) = \text{categorical (discrete)} \]

\[ f(x) = \text{continuous} \]

| $$\mu_x=E[x]$$ | $$\sigma_x^2 = V[x]$$ |

| Binomial | $$n\pi$$ | $$n\pi (1-\pi)$$ |

| Normal | $$\mu$$ | $$\sigma^2$$ |

| Poisson | $$\lambda$$ | $$\lambda$$ |

| Exponential | $$\frac{1}{\lambda}$$ | $$\frac{1}{\lambda^2}$$ |

| Uniform | $$\frac{b+a}{2}$$ | $$\frac{(b-a)^2}{12}$$ |

| Binomial | \[ p(x) = \binom{n}{x} \pi^x (1 - \pi)^{n-x}\] |

| Poisson | \[ p(x) = \frac{e^{-\lambda} \lambda^x}{x!} \] |

| Normal | \[ f(x) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2 \pi \sigma^2}} e^{-\frac{1}{2} \left(\frac{x - \mu}{\sigma} \right)}\] |

| Exponential | \[ f(x) = \lambda e^{-\lambda x} \] |

| Uniform | \[ f(x) = \frac{1}{b-a}\] |

$$\pi = p =$$ proportion

$$n\pi = C = \lambda =$$ mean

$$\mu = n \pi$$

$$\sigma^2 = n \pi (1 - \pi)$$

| Sample mean: $$\bar{x} =$$ | \[ \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n x_i \] | Sample median: | \[\tilde{x} = \text{if } n \text{ is odd,} \left(\frac{n+1}{2}\right)^{\text{th}} \text{ value} \] \[ \text{if } n \text{ is even, average} \frac{n}{2} \text{ and } \frac{n}{2}+1\] |

| Sample variance: | \[s^2 = \frac{1}{n-1}\sum (x_i - \bar{x})^2 = \frac{S_{xx}}{n-1} = \sum x_i^2 - \frac{1}{n} \left( \sum x_i \right)^2\] | Standard deviation: $$s = \sqrt{s^2}$$ |

low/high quartile: median of lower/upper half of data. If $$n$$ is odd, include median in both.

| low = 1st quartile | high = 3rd quartile | median = 2nd quartile |

IQR: high - low quartiles

range: max - min

Total of something: $$\bar{x} n$$

An outlier is any data point outside the range defined by IQR $$\cdot 1.5$$

An

extreme is any data point outside the range defined by IQR $$\cdot 3$$

\[ \mu_{\bar{x}} = \mu = \bar{x} \]

\[ \sigma_{\bar{x}} = \frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}} \]

\[ \mu_p = p = \pi \]

\[ \sigma_p = \sqrt{\frac{p(1-p)}{n}} \]

$$p(x)$$ distribution

[discrete] | mean: $$\mu_x = \sum x \cdot p(x) = E[x]$$

variance: $$\sigma_x^2 = \sum(x-\mu_x)^2 p(x) = V[x]$$ |

$$f(x)$$ distribution

[continuous] | mean: \[ \mu_x = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} x \cdot f(x) \]

median:\[ \tilde{\mu} \rightarrow \int_{-\infty}^{\tilde{\mu}} f(x) = \int_0^{\tilde{\mu}} f(x) = 0.5 \]

variance:\[ \sigma^2 = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} (x =\mu_x)\cdot f(x) \] |

| Normal | \[ k = \frac{\mu + k \sigma - \mu}{\sigma} \] standardize:\[ \frac{x - \mu}{\sigma} \] \[ -k = \frac{\mu - k \sigma - \mu}{\sigma} \] upper quartile:\[ \mu + 0.675\sigma \] lower quartile:\[ \mu - 0.675\sigma \] |

| Exponential | \[ -ln(c) \cdot \frac{1}{\lambda} \text{ where c is the quartile }(0.25,0.5,0.75) \] |

\[ S_{xx} = \sum x_i^2 - \frac{1}{n}\left(\sum x_i\right)^2 = \sum(x_i - \bar{x})^2 \]

\[ S_{yy} = \sum y_i^2 - \frac{1}{n}\left(\sum y_i\right)^2 = \sum(y_i - \bar{y})^2 \]

\[ S_{xy} = \sum{x_i y_i} - \frac{1}{n}\left(\sum x_i\right)\left(\sum y_i\right) \] \[ \text{SSResid} = \text{SSE (error sum of squares)} = \sum(y_i - \hat{y}_i)^2 = S_{yy} - b S_{xy} \]

\[ \text{SSTo} = \text{SST} = S_{yy} = \text{Total sum of squares} = \text{SSRegr} + \text{SSE} = \text{SSTr} + \text{SSE} = \sum_i^k \sum_j^n (x_{ij} - \bar{\bar{x}})^2 \]

\[ \text{SSRegr} = \text{regression sum of squares} \]

\[ r^2 = 1 - \frac{\text{SSE}}{\text{SST}} = \frac{\text{SSRegr}}{\text{SST}} = \text{coefficient of determination} \]

\[ r = \frac{S_{xy}}{\sqrt{S_{xx}}\sqrt{S_{yy}}} \]

\[ \hat{\beta} = \frac{S_{xy}}{S_{xx}} \]

\[ \hat{\alpha} = \bar{y} - \beta\bar{x} \]

prediction:

\[ \hat{\alpha} = \bar{y} - \beta\bar{x} \]

Percentile ($$\eta_p$$):

\[ \int_{-\infty}^{\eta_p} f(x) = p \]

MSE (Mean Square Error) =

\[ \frac{1}{n} SSE = \frac{1}{n}\sum (y_i-\hat{y}_i)^2 = \frac{1}{n} \sum (y_i - \alpha - \beta x_i)^2 \]

MSTr (Mean Square for treatments)

ANOVA\[ SST = SS_{\text{explained}} + SSE \]

\[ R^2 = 1 - \frac{SSE}{SST} \]

\[ \sum(y_i - \bar{y})^2 = \sum(\hat{y}_i - \bar{y})^2 + \sum(y_i - \hat{y}_i)^2 \]

\[ s_e^2 = \frac{SSE}{n-2} \text{ or } \frac{SSE}{n-(k+1)} \]

\[ R_{adj}^2 = 1-\frac{SSE(n-1)}{SST(n-(k+1))}\]

\[ H_0: \mu_1 = \mu_2 = .. = \mu_k \]

\[ \bar{\bar{x}} = \left(\frac{n_1}{n}\right)\bar{x}_1 + \left(\frac{n_2}{n}\right)\bar{x}_2 + ... + \left(\frac{n_k}{n}\right)\bar{x}_k \]

\[ SSTr = n_1(\bar{x}_1 - \bar{\bar{x}})^2 + n_2(\bar{x}_2 - \bar{\bar{x}})^2 + ... + n_k(\bar{x}_k - \bar{\bar{x}})^2 \]

| Sources | df | SS | MS | F |

| Between Samples | $$k-1$$ | SSTr | MSTr | $$\frac{\text{MSTr}}{\text{MSE}}$$ |

| Within Samples | $$n-k$$ | SSE | MSE |

| Total | $$n-1$$ | SST |

One-sample t interval:

\[ \bar{x} \pm t^* \frac{s}{\sqrt{n}} \]

(CI)

Prediction interval:

\[ \bar{x} \pm t^* s\sqrt{1+\frac{1}{n}} \]

(PI)

Tolerance interval:

\[ \bar{x} \pm k^* s \]

Difference t interval:

\[ \bar{x}_1 - \bar{x}_2 \pm t^*\sqrt{\frac{s_1^2}{n_1} + \frac{s_2^2}{n_2}} \]

Adjusted

\[ R^2 = 1 - \left(\frac{n-1}{n-(k+1)}\right) \frac{SSE}{SST} \]

Type I error: Reject $$H_0$$ when true; If the F-test p-value is small, it's useful.

Type II error: Don't reject $$H_0$$ when false.

B(Type II) =

\[ z^* \sqrt{\frac{\sigma_1^2}{n_1} + \frac{\sigma_2^2}{n_2}} \]

Simple linear regression: $$y = \alpha + \beta x$$

General multiple regression: $$y = \alpha + \beta_1 x_1 + ... + \beta_k x_k$$

Prediction error: $$\hat{y} - y^* = \sqrt{s_{\hat{y}}^2 + s_e^2} \cdot t$$

\[ t = \frac{\hat{y}-y^*}{\sqrt{s_{\hat{y}}^2 + s_e^2}} \]

\[ P(\hat{y} - y^* > 11) = P\left(\sqrt{s_{\hat{y}}^2 + s_e^2} \cdot t > 11\right) = P\left(t > \frac{11}{\sqrt{s_{\hat{y}}^2 + s_e^2}}\right) \]

\[ \mu_{\hat{x}_1 - \hat{x}_2} = \mu_{\hat{x}_1} - \mu_{\hat{x}_2} = \mu_1 - \mu_2 \]

\[ \sigma_{\hat{x}_1 - \hat{x}_2} = \sqrt{\frac{\sigma_1^2}{n_1} + \frac{\sigma_2^2}{n_2}} \]

\[ \hat{x}_1 - \hat{x}_2 \pm z^* \sqrt{\frac{s_1^2}{n_1} + \frac{s_2^2}{n_2}} \]

To test if $$\mu_1 = \mu_2$$, use a two-sample t test with $$\delta = 0$$

If you're looking for the true average, it's a CI, not the standard deviation about the regression.

A large n value may indicate a z--test, but you must think about whether or not its paired or not paired.

A hypothesis is only valid if it tests a

population parameter. Do

not extrapolate outside of a regression analysis unless you use a future predictor.

F-Test\[ F = \frac{MSRegr}{MSE} \]

\[ MSRegr = \frac{SSRegr}{k} \]

\[ MSResid = \frac{SSE}{n - (k+1)} \]

\[ H_0: \beta_1=\beta_2=...=\beta_k=0 \]

Chi-Squared ($$\chi^2$$)\[ H_0: \pi_1 = \frac{\hat{n}_1}{n_1},\pi_2 = \frac{\hat{n}_2}{n_2}, ..., \pi_k = \frac{\hat{n}_k}{n_k} \]

\[ \chi^2 = \sum_{i=1}^k \frac{(n_i - \hat{n}_i)^2}{\hat{n}_i} = \sum \left(\frac{\text{observed - expected}}{\text{expected}}\right) \]

Linear Association Test\[ H_0: p=0 \]

\[ t = \frac{r\sqrt{n-2}}{\sqrt{1-r^2}} \]

\[ \sigma_{\hat{y}} = \sigma \sqrt{\frac{1}{n} + \frac{(x^* - \bar{x})^2}{S_{xx}} } \]

\[ \mu_{\hat{y}} = \hat{y} = \alpha + \beta x^* \]

\[ \hat{y} \pm t^* s_{\hat{y}} df = n-2 \text{ for a mean y value (population)} \]

\[ \hat{y} \pm t^* \sqrt{s_e^2 + s_{\hat{y}}^2} df=n-2 \text{ for single future y-values (PI)} \]

Paired T-test\[ \bar{d} = \bar{(x-y)} \]

\[ t = \frac{\bar{d} - \delta}{\frac{s_d}{\sqrt{n}}} \]

\[ \sigma_d = \sigma \text{ of x-y pairs } = s_d \]

Large Sample:

\[ z = \frac{\bar{x} - 0.5}{\frac{s}{\sqrt{n}}} \]

\[ \text{P-value } \le \alpha \]

Small Sample:

\[ z = \frac{\bar{x} - \mu}{\frac{s}{\sqrt{n}}} \]

\[ df = n-1 \]

Difference:

\[ H-0: \mu_1 - \mu_2 = \delta \]

\[ t = \frac{\bar{x}_1 - \bar{x}_2 - \delta}{\sqrt{\frac{s_1^2}{n_1} + \frac{s_2^2}{n_2}}} \]

\[ df = \frac{\left(\frac{s_1^2}{n_1} + \frac{s_2^2}{n_2} \right)}{\frac{1}{n_1-1} \left(\frac{s_1^2}{n_1}\right)^2 + \frac{1}{n_2-1} \left(\frac{s_2^2}{n_2}\right)^2 } \]