Discord: Rise Of The Bot Wars

The most surreal experience I ever had on discord was when someone PMed me to complain that my anti-spam bot wasn’t working against a 200+ bot raid. I pointed out that it was never designed for large-scale attacks, and that discord’s own rate-limiting would likely make it useless. He revealed he was selling spambot accounts at a rate of about $1 for 100 unique accounts and that he was being attacked by a rival spammer. My anti-spam bot had been dragged into a turf war between two spambot networks. We discussed possible mitigation strategies for worst-case scenarios, but agreed that most of them would involve false-positives and that discord showed no interest in fixing how exploitable their API was. I hoped that I would never have to implement such extreme measures into my bot.

Yesterday, our server was attacked by over 40 spambots, and after discord’s astonishingly useless “customer service” response, I was forced to do exactly that.

A Brief History of Discord Bots

Discord is built on a REST API, which was reverse engineered by late 2015 and used to make unofficial bots. To test out their bots, they would hunt for servers to “raid”, invite their bots to the server, then spam so many messages it would softlock the client, because discord still didn’t have any rate limiting. Naturally, as the designated punching bags of the internet, furries/bronies/Twilight fans/slash fiction writers/etc. were among the first targets. The attack on our server was so severe it took us almost 5 minutes of wrestling with an unresponsive client to ban them. Ironically, a few of the more popular bots today, such as “BooBot”, are banned as a result of that attack, because the first thing the bot creator did was use it to raid our server.

I immediately went to work building an anti-spam bot that muted anyone sending more than 4 messages per second. Building a program in a hostile environment like this is much different from writing a desktop app or a game, because the bot had to be bulletproof - it had to rate-limit itself and could not be allowed to crash, ever. Any bug that allowed a user to crash the bot was treated as P0, because it could be used by an attacker to cripple the server. Despite using a very simplistic spam detection algorithm, this turned out to be highly effective. Of course, back then, discord didn’t have rate limiting, or verification, or role hierarchies, or searching chat logs, or even a way to look up where your last ping was, so most spammers were probably not accustomed to having to deal with any kind of anti-spam system.

I added raid detection, autosilence, an isolation channel, and join alerts, but eventually we were targeted by a group from 4chan’s /pol/ board. Because this was a sustained attack, they began crafting spam attacks timed just below the anti-spam threshold. This forced me to implement a much more sophisticated anti-spam system, using a heat algorithm with a linear decay rate, which is still in use today. This improved anti-spam system eventually made the /pol/ group give up entirely. I’m honestly amazed the simplistic “X messages in Y seconds” approach worked as long as it did.

Of course, none of this can defend against a large scale attack. As I learned by my chance encounter with an actual spammer, it was getting easier and easier to amass an army of spambots to assault a channel instead of just using one or two.

Anatomy Of A Modern Spambot Attack

At peak times (usually during summer break), our server gets raided 1-2 times per day. These minor raids are often just 2-3 tweens who either attempt to troll the chat, or use a basic user script to spam an offensive message. Roughly 60-70% of these raids are either painfully obvious or immediately trigger the anti-spam bot. About 20% of the raids involve slightly intelligent attempts to troll the chat by being annoying without breaking the rules, which usually take about 5-10 minutes to be “exposed”. About 5-10% of the raids are large, involving 8 or more people, but they are also very obvious and can be easily confined to an isolation channel. Problems arise, however, with large spambot raids. Below is a timeline of the recent spambot attack on our server:

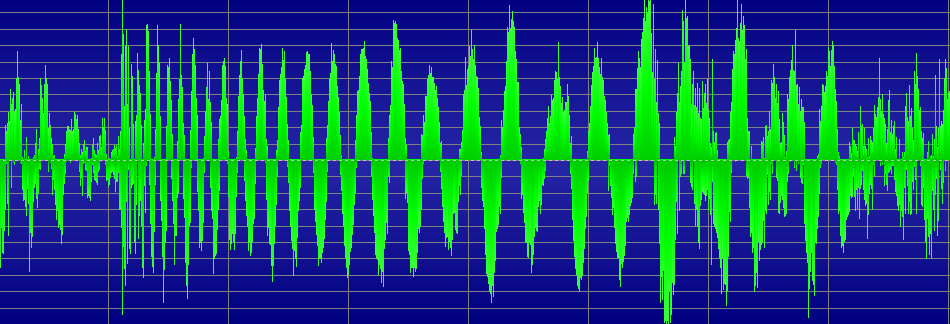

This was a botched raid, but the bots that actually worked started spamming within 5 seconds of joining, giving the moderators a very narrow window to respond. The real problem, however, is that so many of them joined, the bot’s API calls to add a role to silence them were rate-limited. They also sent messages once every 0.9 seconds, which is designed to get around Discord’s rate limiting. This amounted to 33 messages sent every second, but it was difficult for the anti-spam to detect. Had the spambots reduced their spam cadence to 3 seconds or more, this attack could have bypassed the anti-spam detection entirely. My bot now instigates a lockdown by raising the verification level when a raid is detected, but it simply can’t silence users fast enough to deal with hundreds of spambots, so at some point the moderators must use a mass ban function. Of course, banning is restricted by the global rate limit, because Discord has no mass ban API endpoint, but luckily the global rate limit is something like 50 requests per second, so if you’re only banning people, you’re probably okay.

However, a hostile attacker could sneak bots in one-by-one every 10 minutes or so, avoiding setting off the raid alarm, and then activate them all at once. 500 bots sending randomized messages chosen from an English dictionary once every 5 seconds after sneaking them in over a 48 hour period is the ultimate attack, and one that is almost impossible to defend against, because this also bypasses the 10-minute verification level. As a weapon of last resort, I added a command that immediately bans all users that sent their first message within the past two minutes, but, again, banning is subject to the global rate limit! In fact, the rate limits can change at any time, and while message deletion has a higher rate limit for bots, bans don’t.

The only other option is to disable the @everyone role from being able to speak on any channel, but you have to do this on a per channel basis, because Discord ignores you if you attempt to globally disable sending message permissions for @everyone. Even then, creating an “approved” role doesn’t work because any automated assignment could be defeated by adding bots one by one. The only defense a small Discord server has is to require moderator approval for every single new user, which isn’t a solution - you’ve just given up having a public Discord server. It’s only a matter of time until any angry 13-year-old can buy a sophisticated attack with a week’s allowance. What will happen to public Discord servers then? Do we simply throw up our hands and admit that humanity is so awful we can’t even have public communities anymore?

The Discord API Hates You

The rate-limits imposed on Discord API endpoints are exacerbated by temporary failures, and that’s excluding network issues. Thus, if I attempt to set a silence role on a spammer that just joined, the API will repeatedly claim they do not exist. In fact, 3 separate API endpoints consistently fail to operate properly during a raid: A “member joined” event won’t show up for several seconds, but if I fall back to calling GetMember(), this also claims the member doesn’t exist, which means adding the role also fails! So I have to attempt to silence the user with every message they send until Discord actually adds the role, even though the API failures are also counted against the rate limit! This gets completely absurd once someone assaults your server with 1000 spambots, because this triggers all sorts of bottlenecks that normally aren’t a problem. The alert telling you a user has joined? Rate limited. It’ll take your bot 5-10 minutes to get through just telling you such a gigantic spambot army joined, unless you include code specifically designed to detect these situations and reduce the number of alerts. Because of this, a single user can trigger something like 5-6 API requests, all of which are counted against your global rate limit and can severely cripple a bot.

The general advice that is usually given here is “just ban them”, which is terrible advice because Discord’s own awful message handling makes it incredibly easy to trigger a false positive. If a message fails to send, the client simply sends a completely new message, with it’s own ID, and will continue re-sending the message until an Ack is received, at which point the user has probably send 3 or 4 copies of the same message, each of which have the same content, but completely unique IDs and timestamps, which looks completely identical to a spam attack.

Technically speaking, this is done because Discord assigns snowflake IDs server-side, so each message attempt sent by the client must have a unique snowflake assigned after it is sent. However, it can also be trivially fixed by adding an optional “client ID” field to the message, with a client-generated ID that stays the same if the message is resent due to a network failure. That way, the server (or the other clients) can simply drop any duplicate messages with identical client IDs while still ensuring all messages have unique IDs across their distributed cluster. This would single-handedly fix all duplicate messages across the entire platform, and eliminate almost every single false-positive I’ve seen in my anti-spam bot.

Discord Doesn’t Care

Sadly, Discord doesn’t seem to care. The general advice in response to “how do I defend against a large scale spam attack” is “just report them to us”, so we did exactly that, and then got what has to be one of the dumbest customer service e-mails I’ve ever seen in my life:

Excuse me, WHAT?! Sorry about somebody spamming your service with horrifying gore images, but please don’t delete them! What happens if the spammers just delete the messages themselves? What happens if they send child porn? “Sorry guys, please ignore the images that are literally illegal to even look at, but we can’t delete them because Discord is fucking stupid.” Does Discord understand the concept of marking messages for deletion so they are viewable for a short time as evidence for law enforcement?! My anti-spam bot’s database currently has more information than Discord’s own servers! If this had involved child porn, the FBI would have had to ask me for my records because Discord would have deleted them all!

Obviously, we’re not going to leave 500+ gore messages sitting in the chatroom while Discord’s ass-backwards abuse team analyzes them. I just have to hope my own nuclear option can ban them quickly enough, or simply give up the entire concept of having a public Discord server.

The problem is that the armies of spambots that were once reserved for the big servers are now so easy and so trivial to make that they’re beginning to target smaller servers, servers that don’t have the resources or the means to deal with that kind of large scale DDoS attack. So instead, I have to fight the growing swarm alone, armed with only a crippled, rate-limited bot of my own, and hope the dragons flying overhead don’t notice.

What the fuck, Discord.